Steph’s in complete remission despite her delayed HL diagnosis

Over five months, Steph Eliot had a misdiagnosis, then a significant delay in surgery for the open biopsy that finally resulted in her diagnosis with Stage 2 Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

During that time, Steph stopped breastfeeding her youngest child, who had just turned one, when she was prescribed antibiotics for an infection, she didn’t turn out to have.

And the day she got a series of calls – from her GP, infectious diseases specialist, and surgeon – all telling her she had lymphoma, she already knew!

Signs, symptoms, tests, and more tests

Steph’s first symptom was “a tiny bit of discomfort under my left armpit”, felt while packing to go on a cruise in October 2017. She was 35.

“I didn’t give it a second thought,” said the Canberra lawyer and mother of two. Steph had recently returned from maternity leave to her government affairs job, working from home four days a week.

“The pain became more noticeable, so halfway through the cruise I went to see the onboard doctor,” Steph explained.

“She felt the lump, and said that while there was nothing she could do about it on the cruise, I should see my GP when I got back to shore.”

Steph didn’t mention this health issue to the other 15 members of her family she was with, because she didn’t want to worry them.

“I knew cancer was a possibility, but we were on a cruise with a family member with advanced cancer. I didn’t think it was appropriate to add to their level of concern or raise an issue that statistically I felt was probably going to be nothing,” she said.

“I wasn’t too worried about it at that point either, given there wasn’t a whole lot I could do.”

“I remember looking online about the signs of a lump that might be cancer. The general advice seemed to be that it was more likely to be painless rather than as painful as mine was.

“I just thought, ‘oh well, there’s nothing I can do and no point in worrying about it, let’s just enjoy this holiday’, so I did and had a great time.”

Back in Australia, Steph saw her GP, had a fine needle aspiration biopsy under ultrasound, and within a couple of days was told there was no definitive indication of cancer. Next, she had a core biopsy with two samples taken. The ultrasound showed that within two weeks of the earlier ultrasound, there were new small lumps in her chest and neck.

“The doctor said, ‘it is unusual for cancer to spread that quickly. It seems more indicative of an infection, but obviously we need to wait and see what the results say’.

“When they came back, it was diagnosed as a breastfeeding-related infection,” said Steph, something she felt pretty sure she would have known about.

“I thought they had grown a culture that indicated a bacterial infection, not realising at the time that it was a speculative finding.

“I was still breastfeeding at that point,” said Steph, who was referred to an infectious diseases physician.

“At that time, I decided again not to worry about it. I didn’t see the point when there seemed to be a clear diagnosis.

“I went with the treatment and started a course of strong antibiotics. That was when I stopped breastfeeding, in part because I was concerned about the antibiotics travelling through the breast milk.”

For the first few days after commencing antibiotics there was some improvement. But for the following four months, her lump “grew and grew and grew”. In December 2018, she couldn’t lower her left arm to her side “at all”, in January, she was taking painkillers day and night “because the pain levels were quite intense”, and by the time she had surgery the following March, “the original lump was the size of a tennis ball”.

“To accommodate the lump, I’d spend the day with my elbow out to the side and my left hand on my hip. I recall doing a range of activities – from horse riding to presenting to my company’s management board – in this odd position.

“But strangely enough, I still wasn’t that worried about it,” said Steph. “I wasn’t responding to the antibiotics like I should have, so the next stage was to do an open biopsy and remove the lump.

“It wasn’t until March that I was able to get in to see a surgeon and have the open biopsy. Many surgeons take leave over the Christmas period, and by then I’d had two biopsies and four samples and, given they’d all come back with no indication of cancer, I expect I also wasn’t on the high priority list.

“The cancer spread very significantly during those three months.

“By February, I started getting night sweats and muscle fatigue in my legs, but the whole time, from October, I felt great and had no problems. I was active and running in the mornings.

“It didn’t occur to me that I could have quite a bit of cancer in my body and feel so good.”

“It wasn’t until February that I started to think, ‘something’s not right here, my pain levels are high and I’m clearly not responding to any kind of antibiotics’.”

Steph had travelled extensively in developing countries, she’d given a very detailed medical history, and all possible infections that she could have picked up had been researched and nothing came back positive.

“At that point, I was looking forward to the surgery and to getting a clear picture.”

Before having the surgery to remove what was by then “a big ball under my left arm”, Steph had a PET scan.

“When the doctor called, he was a bit cagey about the results, so I thought I better have a look myself,” said Steph, so she picked up her results from pathology on the way to the hospital for her surgery.

“I was by myself at the time and remember steeling myself as I walked through the hospital doors and opened the envelope. I went straight to the end and saw the words, ‘highly suspicious for lymphoma’, and I thought, ‘oh well, now I know’.

“At that stage, my choices were either an infectious disease that was difficult to cure, or cancer. I was more interested in knowing what it was rather than continuing on in the dark, even if the result was going to be less than ideal.

“I don’t generally get anxiety around scans because my theory is that the scan doesn’t change what’s happening, it just tells me what’s already happening, and I would rather know.

“While it wasn’t ideal, I did immediately think, ‘I wonder how treatable this is going to be?’

“After the surgery, the anaesthetist chatted to me, saying, ‘you lost a lot more blood than we thought. It was quite difficult to cut it out and separate it from the remaining tissue’. She was very sympathetic, and I could tell… she thought it was cancer.

“So, armed with her comment and the information on the PET scan, it was no surprise to me when, on one day, I had three doctors deliver the news of what it was. Everyone was on their game.”

Sharing news of her diagnosis

Before Steph had a chance to call her husband and tell him she had lymphoma, she had to go to her Canberra office for an important interview.

“I’d been shortlisted for a job as the business manager to our CEO and had an interview that afternoon. I was getting ready for the interview when I got the first call,” said Steph.

“It was a wonderful career opportunity and I thought it would be unprofessional not turn up to the interview, which was in 30 minutes’ time. I needed to explain that I was withdrawing from the process, so that’s what I did.”

It was a remote interview and the people on the interview panel were the first people to know, then Steph got to call her husband, Nigel, saying, “I need to tell you what’s happened”.

They both met at home and Steph suggested they go to a bar “because I’m probably not going to have wine for a while”, but on the way they were involved in a car accident.

“We were just laughing at that point, we thought this was the craziest set of events. We both had a decent glass of red wine and thought, ‘oh well’.

Getting started on treatment

Steph described her first appointment with her haematologist “as very reassuring”.

“I was fortunate to have a haematologist who I trusted. I knew from the experience of my family member and other patients I met in the chemo ward that not everyone trusted their treating doctor, or felt they were someone who listened to their concerns and answered their questions.

“She said, ‘it’s not ideal that you have cancer, but the cancer you have is treatable and if you go through the treatment your prospects will be quite good. Our rates of success are generally quite good for this one [HL], but I do need to tell you that if you don’t have the chemo you will die’.

“My husband and I later joked about the fact she felt she needed to spell out the consequences of not having chemo, but I can understand why it’s important to do so. It was never a question for me, though – after a long period of uncertainty I was looking forward to starting treatment.

“It was nice at that point to hear that it was a treatable cancer. That took a lot of the worry away.”

Then Steph was asked if she planned to have another baby. If she was, there were potential fertility considerations.

“My husband and I had been thinking of having another child, but with the antibiotics and knowing in the back of my mind that it could be cancer, we decided not to. I’m relieved, because if I had fallen pregnant when we had intended, I would have been diagnosed midway through my pregnancy.”

“We decided not to do any fertility preservation, but to start the treatment as soon as possible.”

Steph worked as usual the following week, which involved going to Sydney for a presentation. She flew home to Canberra on the Monday afternoon, started chemo at 9am the following day, and was able to have the rest of her treatment period off work.

“My employer had arranged income protection insurance on my behalf through a group policy, and voluntarily paid my income for the three-month waiting period before that kicked in.

“So, I had a proportion of my income the whole time I was off, from April to the following January.

“I’m eternally grateful to my employer for that. It took away so much of the financial stress that would have otherwise been there.

“Now I tell others… ‘make sure you get income protection insurance – you never know when you will need it, and once you’re diagnosed, it’s very difficult to get’.”

Treatment challenges and results

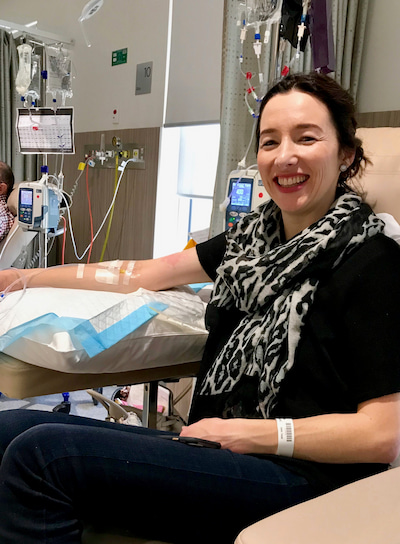

Steph’s treatment began in April 2019. She generally tolerated the six months of the ABVD* regimen well, with no adverse reactions and manageable nausea, but the indirect effects, such as fatigue, were “very challenging”.

“I found the hardest thing during chemo was the fact that, no matter how exhausted or sick I was, I still had to be up early every morning because I was a parent. Some days that was very difficult,” explained Steph.

“The other challenge was that I kept catching bugs off my kids, so I was in and out of hospital due to low immunity. That was disruptive for the family, especially for my husband who was trying to work, support me, and look after the kids.

“I was fortunate to have my parents and my sister in Canberra, who were incredible supports.”

Steph’s haematologist had told her that most people with HL responded very well to the chemo and had a clear PET scan after two months of treatment.

“So that was my expectation, and when I did the scan and went to see her, unfortunately I hadn’t responded as well as we’d hoped, and in addition, there was an enlarged area of activity,” said Steph.

“But I had been unwell, and with PET scans it can be hard to tell infection from cancer. She felt there was a good chance the enlarged node was an infection.”

Instead of dropping the bleomycin, as is standard practice after the first two months, following a clear PET scan, the decision was made for Steph to continue on that drug.

The dawning of another possible outcome

“That month was awful,” said Steph.

“It was the first time I had truly allowed myself to think about what this could mean for me and the family and the first time… that I started planning… for the future of my family if I wasn’t there… sorry,” said Steph struggling with emotion.

“I really hadn’t spent much time worrying. I didn’t have much anxiety the whole time until that month.

“At that point I talked to friends and family. By practising self-care – meditating and walking in bushland near my home – I was able to maintain some perspective.

“One piece of advice I found helpful came from the Coping with Cancer series on the Headspace meditation app. The creator of the app was himself in remission from cancer, and he suggested that for some, the dialogue of ‘fighting’ or ‘battling’ cancer was unhelpful.

“While I can’t remember his exact words, I recall reflecting on this and coming to the conclusion that for me, it was unhelpful to think of the cancer as a foreign invader. These were cells of my own body. Yes, I didn’t like how they were behaving, but they were mine nonetheless. This helped me to accept what was happening without too much friction.

“A couple of times I also reflected on the long period of misdiagnosis, and whether there were things I should have done differently during that time that would have led to a different result. But I ultimately decided not to give these thoughts any air time – what had happened, had happened, and criticising myself wasn’t going to change that.

“I tried not to get too bogged down contemplating the worst possible outcome, and to remember that the enlarged node may well have been a cold.

“But of course, in the back of my mind, I knew that there was another potential option. And having young children, I was very keen to ensure that if there was anything I could do at that point to plan for the future, then I should do that. So I reviewed my will and made plans in my mind.

“But then, at the end of the month, I got a clear scan, so thankfully that period of significant uncertainty for me was relatively brief, but it was a difficult time,” said Steph who had her final cycle of treatment in September.

“I was very happy, very happy to finish the treatment.”

Returning to work and loving it

Steph returned to work in January 2020, starting on three days a week before picking up a fourth day in February.

“I enjoyed returning to work. It was nice to get back to normality, and to have problems to solve that had nothing to do with me or cancer,” she said.

“My employer allowed me to continue to work from home, which helped while my immune system kicked back into gear.

“Then, about eight months after completing chemo, I started having night sweats, and significant fatigue. Some lumps were found on an ultrasound, so I was sure I had relapsed. My husband and I were making arrangements in relation to how we would, as a family, manage that.

“But thankfully it turned out not to be a relapse, but instead a combination of other things. That’s happened to me twice.

“It didn’t occur to me earlier in this journey that once you’ve had cancer, you’re always looking over your shoulder, even when you’re in remission. There’ll always be an element of heightened awareness of potential relapse symptoms.

“But generally, I don’t think about it. It doesn’t worry me on a day-to-day basis. I just live my life and look forward.”

Ongoing late effects

“I’ve had ongoing effects from the chemo and surgery,” said Steph.

“This includes ongoing lymphedema in my left arm, which is well managed now, and significant hormonal side-effects from chemo which took a while to settle.”

“And all the little things. I’m still trying to get my toenails to grow back properly, as a few fell out a long time after chemo ended.

“But I feel good and love my short hair. I don’t think I’ll go back to long hair again,” said Steph.

When Steph spoke to Lymphoma News she had been in complete remission for 20 months and was 37 years old.

“I now take control of my own healthcare and I’ve learned that you need to understand your condition and own your health; you cannot delegate it to a system. A few things have reinforced that to me.

“One was when my haematologist went on leave and the stand-in haematologist wanted to give me a particular treatment for neutropenia. I had a very low white blood cell count and was frequently ill,” said Steph.

She got a call from the nurse in the chemo ward saying what he had prescribed for her to have when she next came in.

“I remember thinking, ‘hang on, I’m sure she [her primary haematologist] said I shouldn’t have that’, said Steph.

So when she went into the ward, she spoke to a nurse she trusted, who said she had the authority to choose what happened to her, so she declined the treatment.

“When my treating haematologist came back, she was surprised that he had tried to give me that particular treatment.

“There’ve been quite a few times like that when I’ve had to stop things from happening or find out what the cause of an issue was, and I’ve done a fair bit of problem solving myself throughout this journey.”

Advocating for others on behalf of the Leukaemia Foundation

“My day job is advocacy. I meet decision-makers, bureaucrats, members of parliament and talk to them about things that are important to the industry I work in and our customers.

“It occurred to me that I’m in a good position to advocate for myself, and when things didn’t go according to plan, or when I felt things weren’t right, I was able to do that. But I’m conscious that is not the case for everyone.

“Some aspects of my own treatment, such as the delay for surgery, turned out to be okay in my case, but for someone else that could have meant the difference between life and death,” said Steph.

She offered to support the Leukaemia Foundation’s advocacy efforts and at a media event at Parliament House, attended by the Health Minister, Greg Hunt, in March 2020, Steph briefly gave a sense of her own story as a blood cancer patient.

“I took the opportunity to speak to the Minister, saying, ‘there was this delay and for me that turned out to be okay, but I was surprised that in a country like Australia there could be such a significant delay in being able to access an essential procedure’.”

Steph finished this interview with her key piece of advice for others. “At times it was tempting to fall into ‘if only’ thinking when things weren’t going according to plan, such as ‘if only I had questioned the initial diagnosis, I wouldn’t be in this situation’. By learning to accept my situation as it was, and to let go of anxiety about the parts I couldn’t control, I had the space to influence the parts I could. This didn’t happen automatically. I had to work at it – and still do at times – but I’ve learnt that I can live my life without letting uncertainty get in the way.”

Share your own blood cancer story

Every person touched by blood cancer has a unique and important story to tell. Stories are our most powerful tool to spread awareness of blood cancer, to inspire others going through a diagnosis and to encourage support from the wider community.

* ABVD is a combination of four chemotherapy drugs – doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine.