Graeme’s amazing CAR T-cell therapy story – relapse to remission in 28 days

Just 28 days after Graeme Ardern had CAR T-cell therapy on the CARTEY1 clinical trial, he received the most amazing news – he’d had a complete metabolic response.

For the first time in 15 years, there was no evidence of the follicular lymphoma he’d been diagnosed with in 2006.

Comparing PET scans – one taken before his immunotherapy infusion in Brisbane in November 2021 and the other a month later – Graeme describes the difference as “incredible”.

“I feel positive and it’s the first time in a long time that I’ve been able to look forward,” he said.

At the end of every prior treatment, including chemotherapy and a stem cell transplant, Graeme had known that the disease was still there and would come back, but nobody could tell him when.

“It’s like living with this time bomb and it stopped me from looking too far into the future.”

But Graeme no longer feels that way.

Follicular lymphoma was Graeme’s second lymphoma diagnosis

Graeme, 47, of Beerwah on the Sunshine Coast hinterland in Queensland, has had two different lymphomas in his lifetime. He was first diagnosed with lymphoma as an 11-year-old after being unwell “for a while”.

“They struggled to diagnose it,” said Graeme, who was in fourth grade when his parents were told he had nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma.

“I was considered terminal, with two weeks to live.”

His parents gave their permission for him to proceed with trying the only treatment option at the time – an adult dose of the chemotherapy regimen, MOPP, which Graeme said, “they don’t do anymore”.

The treatment was “very brutal” said Graeme about the several rounds of chemotherapy and radiotherapy he had.

“I went into remission and had quite a few years cancer free… right up until 2006.”

Over the years, however, he’s had problems (late effects) as a result of the treatment he had as a child.

“I’ve burnt very easily in the sun,” said Graeme who’s also had ongoing teeth issues because he doesn’t produce much saliva.

“And my eyes are often very, very dry and my lower eyelashes never came back.”

Just before his 31st birthday, Graeme hit his head “quite hard” at work which resulted in a feeling of nerve tingling down his arm.

“I’m a 12-volt electrical technician but I wasn’t working in my trade at the time, I was in construction, doing aluminium and glass balustrades on high-rise buildings.

“I was lucky in a way,” he said, because he had scans to check for any damage from his head injury.

The radiographer, noticing a lot of osteoporosis in Graeme’s neck, asked his doctor about his radiation history. Looking at the scans again, the radiographer found Graeme had a large lymph node. A full scan revealed he had “large lymph nodes everywhere” and a biopsy identified that he had Stage 4 non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

“It was fortuitously picked up. The only reason they found out early was because I hit my head,” said Graeme who didn’t have any symptoms.

“We were sent to see an oncologist at Nambour who said, ‘there’s nothing we can do for you. At best, you have five to 10 years. Go and spend your time with your family’.”

Graeme wasn’t offered any treatment.

“It was just before rituximab came out on the PBS in August 2006,” said Graeme’s wife, Mandy.

The couple sought a second opinion and were told the same thing “in a much nicer way”, said Graeme.

“Then we decided to see if the oncologist who treated me when I was 11 was still practising, and he was.”

It was Brisbane’s first clinical haematologist, Dr Trevor Olsen, who advocated for vital medical equipment for blood cancer patients almost 50 years ago, and was also a former Medical Advisor and President of the Leukaemia Foundation of Queensland, which was formed in 1975.

“We found Trevor. He was semi-retired, and we saw him privately,” said Graeme.

“He said, ‘yes, you are technically terminal, there’s not a lot of treatment available for you at this point, but we can get ready for the fight that’s coming’, which no one else had offered.

“He put me on to Simon Durrant [a bone marrow transplant specialist] and after four rounds of rituximab, starting in November 2006, Graeme’s stem cells were collected in anticipation of a bone marrow transplant “down the track”.

“Those cells just stayed in storage for 12 years. They said they wouldn’t treat me until I had symptoms, and I wasn’t feeling unwell,” said Graeme, who described himself at that time as “fit and strong”.

“Trevor said, ‘if there’s anything you want to do, you should probably do it now, just in case’

“So we packed up, rented our house out and went around Australia. That was in 2009 and it was magic.”

At the time, their son, Dean was three years old.

“We had a four-wheel drive and an off-road caravan, so we were able to be very self-sufficient in the middle of nowhere for as long as we wanted to really,” said Graeme.

Graeme became symptomatic and started treatment

The first sign that Graeme’s health was changing was in July 2010. The Arderns were in Darwin and a blood test showed Graeme’s platelet levels were dropping.

“Trevor Olsen said he wasn’t too concerned about it at that time and Graeme didn’t have any symptoms,” said Mandy.

“When we were in Derby in Western Australia, Graeme got a cold that he really struggled to get over. We stayed there for a few weeks while he recovered.

“Then, when we were just north of Bunbury, we went for a nature walk. We were doing 10-12km walks every day. This particular walk was 1.5km and Graeme got back to the car half an hour after Dean and me.

“We looked at each other, and when we got back to the car after breakfast, Graeme said, ‘I think we need to get to a doctor’,” said Mandy.

Graeme had a blood test in Bunbury but overnight his lymph nodes came up everywhere and he started scratching like crazy “with that typical lymphoma itch I remembered from when I was young”, he said.

“The next morning, we didn’t even wait for the blood test results. We just packed up and started heading home. We knew it was on,” said Mandy.

“Once the lymph nodes came up, it was pretty undeniable,” said Graeme.

“Then Trevor contacted us and said, ‘you need to be home yesterday’.

“We drove pretty much nonstop then, from Bunbury to here in four days. When we got home. I went straight to the Royal Brisbane for R-CHOP*. I had six rounds which started on New Year’s Eve 2010.”

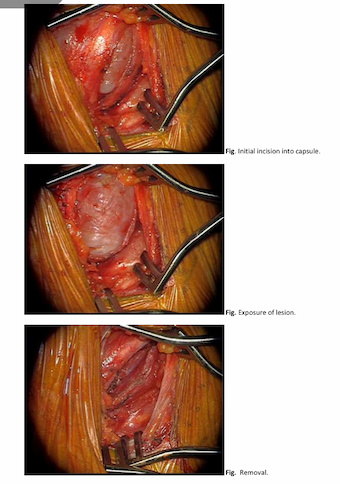

Graeme finished this treatment in July and went on maintenance therapy (rituximab). In September he had a PET scan, and a nerve sheath tumour in Graeme’s neck, that he had long known about and which, until then had been benign, lit up for the first time. It had originally occurred at the site of the biopsy and radiation he’d had during treatment when he was 11.

“By this time, we weren’t seeing Trevor anymore. He’d put us on to Dr Ashish Misra and he said, ‘we need to get that out’,” said Graeme.

The position of the tumour made its removal a tricky procedure and Graeme was referred to a spinal neurosurgeon in Sydney.

“No one else in Australia would touch it,” said Graeme.

“It was our anniversary in September 2011 when we went and saw him,” said Mandy

“He said he could get it out but there was a 30% chance Graeme would lose the function of his left arm, and the cost of the procedure was $30,000.

“The operation was booked for the 10th of October 2011; we had four weeks to come up with the $30,000.

“We came home and all our friends and family helped us raise $30,000 in time for the operation, which was absolutely awesome and we are forever grateful,” said Mandy.

The operation went smoothly and while Graeme had a lot of nerve pain, after having two years of physiotherapy three times a week, he now has almost full function of his arm, although “the nerve pain is still quite bad”.

“I’m on quite a bit of medication for it, but I’m alive and I can use my arm, so it’s not bad,” said Graeme.

Graeme’s relapse and autologous stem cell transplant

In Mandy’s words, life over the next seven years “remained uneventful”. Graeme continued on his maintenance therapy for four and a half years, but things changed again in 2018 when his dad**, Murray was in palliative care.

“Graeme was getting really run down. We knew something was going on because his platelets and bloods started dropping again,” said Mandy.

A month after Graeme’s dad passed away, his haematologist on the Sunshine Coast sent him off for a CT scan. This showed his lymph nodes were up and there was lymphoma in his bone marrow again too.

After four rounds of R-ICE, preparations began for Graeme to have an autologous stem cell transplant in Brisbane, which he had on 20 December 2018, using the stem cells that had been harvested in 2006. The next day he was transferred to hospital on the Sunshine Coast to recover and didn’t have any major issues.

“To be honest, that whole process was pretty brutal,” said Graeme, but he did “everything possible to stay active, which I think definitely aided my recovery”.

“Every morning I forced myself to get out of bed and get dressed, like I wasn’t sick – that seemed important for me. And every day I’d walk, and I rode an exercise bike while in hospital.”

While he was laid low for six months, he gradually built up his stamina.

“Everything cruised along quite well until last year,” said Mandy.

“From around March 2021, his platelets had been dropping again and on Dean’s birthday – June 25 – the haematologist said it was time for scans and a bone marrow biopsy again.”

The results showed Graeme was relapsing again.

“They were saying my treatment options were getting thin, because I’d had so many treatments over the years,” he said.

Graeme relapsed again and had three options including CAR T-cell therapy

Graeme had three options. More chemo, which probably wouldn’t keep him in remission very long, an allogeneic transplant (using matched stem cells from a donor which they would have to find through the Australian Bone Marrow Donor Registry), or Graeme could be “put up for a CAR-T trial”.

This presented him with the opportunity to potentially access CAR T-cell therapy on a clinical trial as he was not eligible to access this treatment through the Medicare Benefits Scheme.

“We’d heard a lot from Graeme’s haematologist about CAR T-cell therapy and how it was a big thing. He’d come back from a conference in America and was super excited about this treatment which he thought was going to cure leukaemia and lymphoma in the future,” Mandy explained.

“That was back around 2013/2014 and he told Graeme, ‘I have a new goal. My job is to keep you alive long enough until this treatment becomes mainstream’.

“So when Graeme was offered CAR-T, we knew a lot about it. Obviously, we did our own research and we agreed for them to put his name forward for the trial,” she said.

“I’ve been put up for trials before but didn’t get into them. I didn’t meet the requirements because my history is so long,” explained Graeme.

“But this time, it didn’t seem to matter. They were quite happy for the long, complicated history.”

Graeme was sent information about the CARTEY1 clinical trial and the risk involved, which he read through, then decided to accept. He and Mandy went down to Brisbane and met Dr Siok Tey (a former Leukaemia Foundation PhD scholarship recipient) in August 2021.

“It was the first time that they had genetically modified the T-cells in Brisbane rather than sending them over to America,” said Graeme, and this meant a two-week, rather than a two-month turnaround time.

Graeme was the second person to participate in the trial.

“We used to joke around. We’d call him the lab rat number two,” said Mandy.

“You’ve got to have a sense of humour, don’t you?” added Graeme.

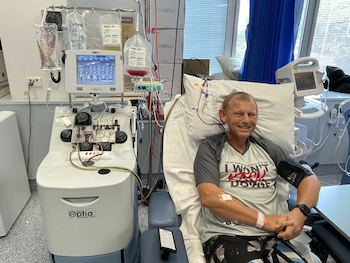

His T-cells were collected on November 3, he had three days of chemo from November 10-12, he was admitted to hospital on the 14th and Graeme had his CAR T-cell infusion on November 15.

The Ardern family had moved to Brisbane on November 7. They stayed at the Leukaemia Foundation’s Village Green accommodation at Bowen Hills, and Dean, who was 15 at the time, started hospital school the next day, which he loved. Previously, Mandy had stayed at Herston Village when Graeme had his stem cell transplant in 2018.

“They’d take me to the hospital and bring me back every day,” she said about the Leukemia Foundation’s transport service.

Describing how having this accommodation helped, Graeme said, “the difference it made to me and our family was incredible and genuinely priceless”, and “I don’t know how I would’ve done it without it, to be honest”, said Mandy.

Last year, they stayed at the Village Green until 17 December, when Graeme got clearance to go home.

“The CAR-T comes with a high risk of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) which is an inflammatory response,” explained Graeme.

He got some fevers, then one afternoon, Graeme’s smart watch set off a high heart rate alert and suddenly he began shaking uncontrollably. His temperature was 39 degrees and his blood pressure plummeted, even though he was still talking and feeling okay.

“They ended up giving him some medication to reduce the CRS – just one dose, to settle it down a bit,” said Mandy.

“I recovered from that quite well and was sent back to the ward,” said Graeme, “and then, from that point, I just kept active again as best I could”.

“I think the difference between having a stem cell transplant in 2018 and the CAR-T was indescribable. Even though I had the CRS and a couple of nights in ICU, the CAR-T was so much better to go through.”

Graeme was discharged on November 27.

“He came back to the unit with us, and we continued walking every day. There’s plenty of parkland around so you could get out and do exercise and be away from people,” said Mandy.

“He had to go to the hospital every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, just for check-ups, and we came home the week before Christmas,” said Mandy.

For the first two months after Graeme’s CAR T-cell infusion, he had to do brain tests three times a day to check his memory and ensure his brain was functioning correctly.

“Nurses did it while he was in hospital, then I had to do it with him at home, and that was to check for neurotoxicity,” said Mandy.

“If he had failed any one of those tests in that time, I was to call an ambulance straight away and get him to the hospital.

“That was the risk involved in the whole process. But thankfully, he didn’t have any of that, so we were very lucky.”

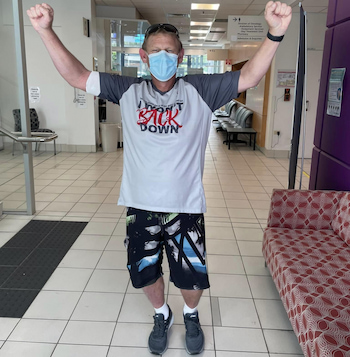

Graeme had a PET scan and bone marrow biopsy the Monday before going home, on the 13th of December, and on the 16th of December they told us he was in remission, said Mandy.

“It is really amazing what they achieved in 28 days.”

Graeme has continued to have scans every three months and the news has continued to be good. At his 12-month one, in December 2022, he still showed a complete metabolic response (remission).

“I feel amazing,” said Graeme, although he’s still recovering.

“I still haven’t got much of an immune system, so I’ve spent a lot of this year sick with colds that tend to stay with me for a long time. So I haven’t had a chance to get really fit and healthy again yet. Hopefully, that’s coming.”

When he spoke to Lymphoma News, Graeme had just had his third immunoglobulin infusion which he has weekly, and which Mandy now administers to him at home.

Grateful for the opportunity to have CAR T-cell therapy

Having come out the other side after CAR T-cell therapy, Graeme says he’s feeling survivor’s guilt – “a bit more this time”.

“I feel incredibly lucky and grateful that I keep responding well to treatment, but I also feel very deeply for everyone who didn’t or has lost someone who didn’t,” he explained.

Mandy said, “we were extremely lucky to be given the chance to have CAR-T and we just always felt like we were in the best possible hands with Dr Cameron Curley, Dr Siok Tey, Dr Andrea Henden, Dr Josh Richmond and a couple of nurses. We never ever questioned or doubted [our decision]”.

“Follicular lymphoma is considered treatable but non-curable,” said Graeme.

“Once it became symptomatic, they could always treat it, but knocking it back becomes a little bit less likely every time.”

“At this point, Graeme has no B-cells and that gives us comfort,” said Mandy.

“He had B-cell cancer, and so as long as he has no B-cells, then he can’t have that cancer. But because he’s got no B-cells, he’s missing half of his immune system pretty much.”

Graeme said he’s still unable to work, “not because of the lymphoma, it’s the issues I have with the nerve damage to my left arm from the tumour” and the medication he takes for this chronic condition.

“We’ve swapped roles,” said Mandy who is a bookkeeper.

“I work and Graeme became the house husband.”

The Arderns have faced some financial difficulties, particularly in 2011, when they had to muster the funds for the operation Graeme had in Sydney to remove the tumour.

“That was a little bit difficult because we had been away for two years, and I wasn’t working when we were on the road,” said Mandy.

“So financially we found it a little bit tough then. My parents had lent us money back then and the Leukaemia Foundation helped us with electricity bills and with transport when I was staying at Herston Village in 2018.

“They’d take me to the hospital and back every day.

“That was great because the cost of parking down there [in Brisbane] is crazy. We spent $2,700 in parking that year,” said Mandy who sometimes went back and forth to the hospital a couple of times, which cost $40 a day in parking.

Getting life back on track

Graeme is a keen mountain biker, and his favourite tracks are the mountain bike trails at the Parklands Conservation Park on the Sunshine Coast. He had a couple of rides there after his CAR T-cell therapy but not since March when he started getting sick.

“We’d love to take another year and finish our trip around Australia, from Bunbury back around to home, particularly Victoria and South Australia which we had to bypass,” said Graeme.

“Dean is about to start senior at school so we’re figuring out how we’re going to work all that,” said Mandy. “We’ll probably stay put until that’s over.”

“We’d planned to go in 2020, but then COVID hit, and everyone went into lockdown, and we weren’t quite ready financially at that point.”

*R-CHOP: an immunochemotherapy regimen of five drugs – rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

**Graeme’s dad was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in 2008 at the age of 70. He had the same R-CHOP treatment as Graeme had and, afterwards, he got on with life until he got prostate cancer and he didn’t respond to the radiotherapy.

Last updated on January 3rd, 2023

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.