Expert Series: the healing power of music therapy

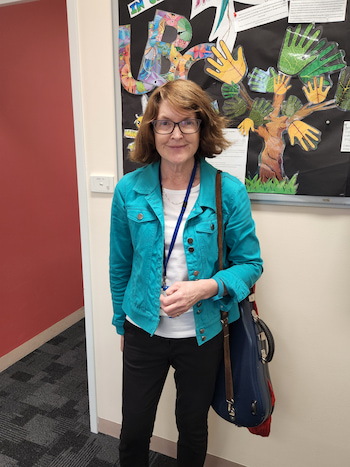

“Music is very much part of our lives” and that’s why it’s such a useful and effective tool in therapy, according to Tasmanian registered music therapist, Dr Stephanie Thompson.

“Music is a different language, and music therapy is like having a conversation, but we use music instead of words,” explains Dr Thompson, who is also a highly qualified psychotherapist, musician, hypnotherapist, and researcher with the Tasmanian Specialist Palliative Care Service, in Hobart, and the Hobart Counselling Centre.

Music therapy is a form of psychosocial and emotional support for a wide range of people, from those recently diagnosed with a blood cancer or going through treatment through to the recently bereaved. Many others benefit from music therapy too, including children with disabilities and people with dementia.

“We can get stuck with words, and the beauty of music is that it’s another, creative way of expressing how we feel.”

“It’s therapy using music and people don’t necessarily think about it as an option. They tend to think, ‘I can’t do that because I’m not a musician’ or ‘I don’t really like music’, or ‘I can’t play an instrument’.

“That’s not the case at all. There’s absolutely no need to be musical to take part in music therapy or to benefit from it.”

Playing an instrument, songwriting, a calming background to enhance sleep, a guide to somewhere peaceful in our mind, even avoiding a tune that triggers a strong emotion. These are all forms of music therapy which Dr Thompson says, “isn’t a new thing”.

While it didn’t emerge as a profession until the 1940s-50s, music therapy dates back to ancient Egypt hieroglyphs and has been used through the ages to heal.

“Often the shaman was a musician and would use music to heal.”

In the mid-1850s, doctors noted significant results in the recovery of patients injured in the Crimean War after musicians played to them in London hospitals. Later, during World War II, when music was used to treat returning servicemen suffering from shell shock and complex trauma, they experienced a sense of calmness.

“There’s plenty of credible evidence-based research to illustrate the efficacy of music therapy.”

Music motivates, persuades, and is emotive

“Music can be a really good motivator and it can be very persuasive,” says Dr Thompson.

At the gym, people work faster and harder on the equipment as the speed of the background music increases, and when driving, hearing a tune we really like can motivate us to press down on the accelerator.

We learn advertising jingles because we hear them over and over again, and in films, a change in the music score can signal the baddies are coming or a love scene.

“And music is very emotive – that’s why it’s useful in therapy, because everybody can relate to it, and because the brain is multi-wired, we can still respond to music, irrespective of having an illness or injury.”

Music as a form of therapy

Music therapy can reduce a range of conditions including loneliness, anxiety, depression, insomnia, agitation, restlessness, even wandering, and it can be used to improve speech, memory, and language.

For someone who has tried many other therapies, Dr Thompson said music therapy may help because it’s so different.

A music therapist works as part of a multidisciplinary team, just as an occupational therapist does, or a physiotherapist, or psychologist, attending multidisciplinary meetings and providing feedback.

“We use music to actively support people of all ages to improve their health, functioning and wellbeing, to manage their physical and mental health, and enhance their quality of life,” says Dr Thompson.

She uses music therapy differently in different clinical settings and because of the dynamic nature of this intervention, Dr Thompson works with whatever is going on with a person at the time, and how well they are too.

“My music therapy practice interventions in grief and bereavement and in palliative care are very different to how I would use music working with a child with special needs, because each of their needs is different.

“If somebody is recently diagnosed or recently bereaved, my role is to spend time with them, in the clinic, at the bedside or in their home, and I find out what’s going to be useful for them.”

For those in mourning, in pain, or in emotional distress, music therapy can help them to feel differently.

“It can be calming, it can soothe us to sleep at night, and it can give us a bit more control. And for those going through treatment, music therapy can reduce nausea and vomiting.”

Music therapy is a creative process and there’s no sense of getting it wrong. It’s a fluid practice with many different interventions and ways of working. And, during a music therapy session, which may vary in time from 10 minutes to an hour, the silence can be just as important as the sound. Listening is really key, said Dr Thompson.

Stephanie Thompson’s training to become a registered music therapist

Music therapy is live music “because it’s dynamic… it’s in the moment”, it’s not pre-recorded.

Therefore, Dr Thompson says, “you need to know something about music before you can even think about training as a music therapist”.

“To do music therapy, you need at least grade eight standard in one instrument and grade five in a second study instrument.

“Violin is my principal instrument, and the piano is my second.”

Everyone in Stephanie’s family plays an instrument and she was seven when she first picked up the violin.

She began a music degree at the Conservatorium of Music in Hobart before transferring to the University of Melbourne where she could combine music and psychology – something she’d always wanted to do. After completing the four-year degree in music therapy, a scholarship took her to the UK, with placements in London and Hertfordshire before doing a master’s degree in psychotherapy.

When Stephanie returned to Australia, her PhD combined music therapy and psychotherapy with research focused on women living with breast cancer.

Instruments and interventions used in music therapy

Dr Thompson feels the rewards of being a music therapist every day.

“It’s a privilege being with somebody and providing sessions for them because I know it’s never easy for them to come into the room or to allow me into their space.

“And it’s a privilege to support somebody at such a delicate time.”

“Anybody can benefit from music therapy if they’re willing to give it a go because we can all respond to music,” she explains.

“We use a number of different instruments and use different musical scales, and a pentatonic scale [a musical scale with five notes per octave] is commonly used which allows people to improvise feely. As it doesn’t matter how they’re played, you can get satisfaction and achievement from being able to play an instrument.

“Even if you don’t have a background in music, you can still make a sound and play something.”

Dr Thompson has adapted the chord harp for music therapy by removing the bars and tuning it to a scale that’s easy to use.

“When patients play the chord harp they can also feel the vibrations in their legs, which is really important if they’re bedridden or for someone who feels disconnected from their body,” she explains.

“We can use elements from nature as well, like leaves, feathers, rocks, and stones to create a particular soundscape to depict and externalise how someone’s feeling.

“What I do, as a music therapist, is encourage my patients to play and then I play with them. It’s like having a conversation but it’s a musical conversation, and it’s improvised.

“I think sometimes we can get really caught up with trying to find the right word. By being creative we can bypass that and get to the core of something.”

A music intervention Dr Thompson uses is music and imagery, and she gave an example, working at someone’s bedside.

“I play my guitar according to their respiratory rate, then manipulate the music to bring a person’s breathing rate down to a deeper level, that allows the music to guide them, so they can travel in their mind to somewhere that’s peaceful and beautiful.”

Other interventions include music and movement which can be used to improve a person’s gait (their walking pattern), a musical life review looks at songs and recording memories, and there’s composing, which is writing music.

For people who are bereaved, Dr Thompson said memory recall can unpack some of their memories by encouraging them to catalogue the music that was significant to the relationship they had with the deceased person by recalling significant events and the songs that went with them, or that person’s favourite music.

“It’s like having an anthology of the relationship with living sound. It can be quite comforting at times and it’s another way of sharing what we know about that person with other family members.”

Externalising our feelings through songwriting

The purpose of music therapy as a psychological intervention differs according to the different clinical populations Dr Thompson works with.

“In palliative care, working with people who are in pain, it’s to help reduce their pain. If they’re feeling emotional distress, it’s to help them to externalise and process what’s happening to them.

“Sometimes words can feel like they get in the way but by externalising something through music, we get to the core of it and we’re able to have a sense of relief in another way.

“Songwriting enables people to externalise their own feelings or how they feel for someone else by putting them into a creative artform.”

Dr Thompson does a lot of songwriting with people who are grieving, which she says, “can be very powerful” for them.

She helps them create a song about how they are feeling now, what they remember about their life with the person who died, their love for that person, and their relationship now.

“For me, it’s such a privilege to be somebody’s voice, and for the person I’m working with, it can be quite transformational.”

Dr Thompson shared an example of the songwriting process and outcome for a man whose daughter was dying. He was feeling helpless because he couldn’t change what was happening with her health and he was grieving about not seeing her grow up.

“The song he wrote was about his hopes and wishes for her and his love for her.”

“We had several sessions together. He would cry a lot, then he’d talk to me about her – what she was like, what she loved, and what they liked to do together.

“I’d write down everything he said, then read back and ask, ‘what’s the most important thing that stands out for you?’

“We organised the words he mentioned and grouped them into phrases, and he decided on the musical style he wanted.

“It was very much his process. He shaped the whole piece,” she explains.

“To finish, I played it back to him, made any changes he wanted, then I recorded it because he found it too hard to sing.”

When he listened to the recording, it was his voice he heard about what he wanted and his wishes for his daughter, and he asked Dr Thompson to sing it on his behalf at his daughter’s funeral because he wanted his words to be heard for his daughter.

“It isn’t ever easy to sing at someone’s funeral, but it’s an enormous privilege and I make sure I rehearse a lot,” laments Dr Thompson.

How music therapy can help

Music therapy can help so many people because most people can respond to music in some way which can be useful.

“When we’re deep in grief, we’re more sensitive to everything around us – to songs, sounds, scents – and almost everything reminds us of that person,” said Dr Thompson.

“With music we can have a bit of control and take care of ourselves when we know we don’t want to listen to some pieces of music because they’ll transport us back to somewhere we’re just not ready to go to yet.

“If we can’t sleep at night and it feels very lonely, music can help us with our breathing, in terms of relaxing and filling in that silence. If we can find a piece of music that’s soothing in terms of its meter and has a regular structure, it can have the effect of being quite calming.

“The reason I play something repetitive is that music tells a story, and we listen to where the story is going. When music is repetitive, you don’t have to listen to what’s happening next in the story so you can feel you’re in a safe environment, in a space that’s completely contained, and just relax and give in to the experience.

“And if I’m working in somebody’s house, I’ll say, ‘I’ll let myself out’.”

“There may be other family members in the room as well and everybody can just be in that space together without the need to say anything, just closing their eyes and having an experience of being supported.

“Often, if people are in pain, they’ll notice the perception of their pain changes too.”

For someone with a neurological impairment, Dr Thompson said music therapy can improve memory. She shared details of a person she is working with who has advanced Alzheimer’s disease, who can’t dress themself or make a cup of tea and has forgotten where they live.

“They are not able to care for themself but can still play their harp. Each week, when I see them, they’re able to focus for a whole hour and improvise [on their harp] and initiate and express themselves. That is meaningful for them because they feel that they’re a functional human being.

“They know who I am, they know who their relatives are, and the ongoing effect lasts for several hours afterwards.

“That has an impact on the family as well. They see this person coming to life; they’re suddenly back again.”

Find a registered music therapist

Music therapy is an evidence-based allied health profession. You can be referred to a music therapist by your GP, another therapist or you can refer yourself. There are more than 300 registered music therapists in metro and regional/rural areas across Australia. A directory of registered music therapists is available on the Australian Music Therapy Association’s website: austmta.org.au.

Last updated on April 5th, 2023

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.