Deborah’s one of the first Aussies to have CAR T-cell therapy for CLL

Deborah Henderson, one of the first Australians to have CAR T-cell therapy for CLL, was back at work within a month of having the new form of immunotherapy in hometown Melbourne.

And now, the mother of three is officially ‘a genetically modified human being’ after having an infusion of her own re-engineered T-cells in September to treat her aggressive CLL.

Diagnosed at 38, Deborah, now aged 47, had failed chemo (FCR), failed a novel therapy (venetoclax [Venclexta®], and was on her second novel therapy (ibrutinib [Imbruvica®) when she went on an international CAR T-cell therapy trial.

“I’ve lost track of how many days because I’m not even counting anymore, because my life’s back to normal.”

This is the story of how Deborah got on that trial, due largely to her own self-advocacy efforts.

The previous time CLL News spoke to Deborah was in 2016, a year she describes as “all a bit of a blur from permanent jet lag”.

When her appointments stretched out to being three-monthly, in 2017, this “took a bit of pressure off” for her.

“I would fly to London, mainly to get the drug, three months’ supply. I’d get a blood test, see my consultant, then fly home,” said Deborah.

“Then, in 2018, I was told the trial was ending; they’d got the data they needed.”

At her last appointment in London in April 2018, she was given two months’ supply.

The drug’s manufacturer, AbbVie, then granted Deborah compassionate access to venetoclax in Australia… right at the time when the drug stopped working for her.

When she went to the Peter McCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne to pick up her venetoclax, she had a blood test.

“That test showed I was no longer MRD negative; they found some CLL,” said Deborah.

She was devastated by this finding.

“I was really sad because I was the beacon of hope for this disease.

“Venetoclax is an amazing drug and I’d had so little side effects from it. I was truly grateful it had given me a four-year remission and had beaten my disease down in a way chemo had never achieved.

“I’d had a completely normal life for four years on that drug, with the exception of having to fly to the UK so much to get it.”

On March 1 last year, ventoclax became available through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for Australians with relapsed/refractory CLL.

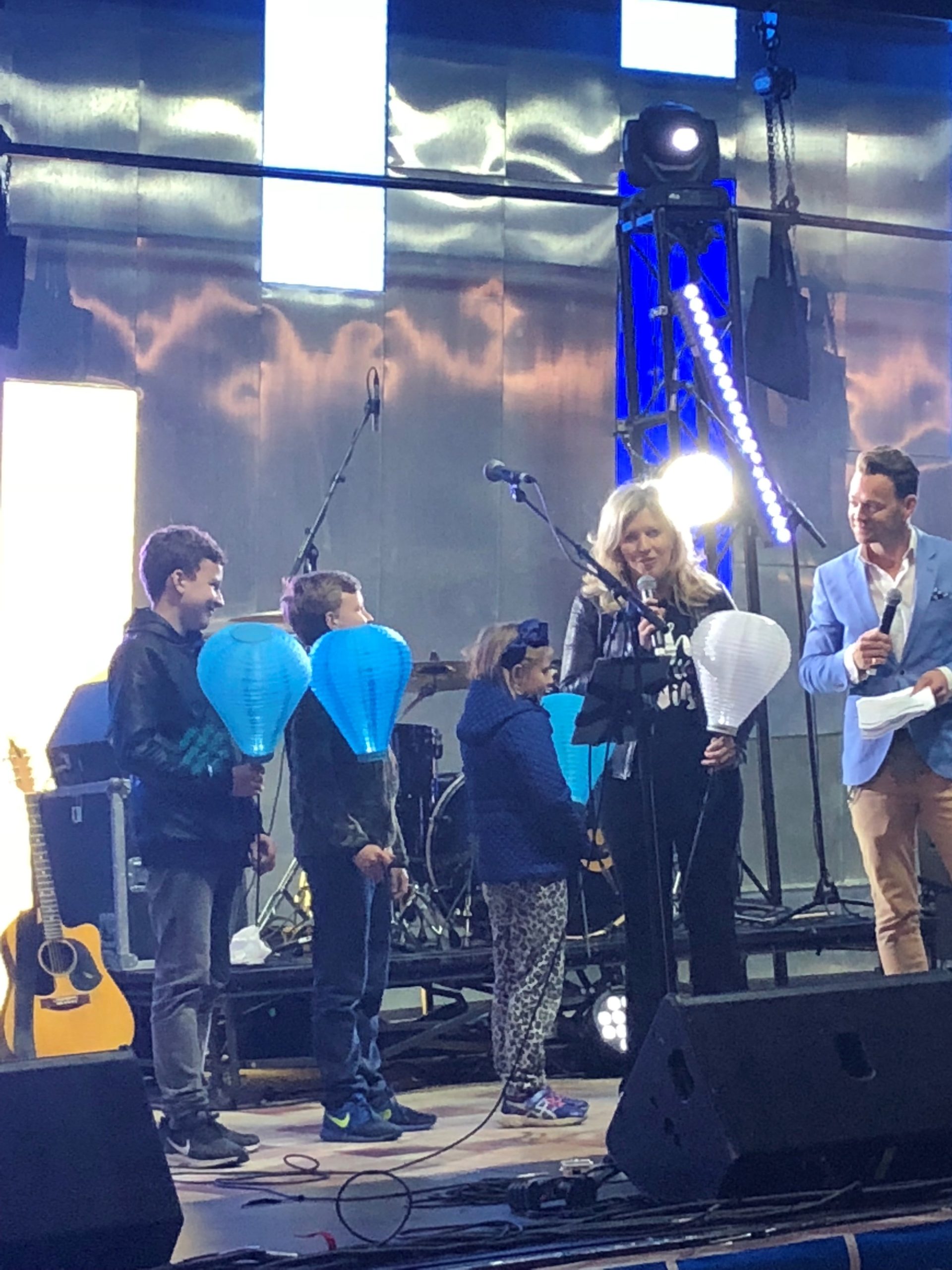

“I was delighted to help with the campaign to get it listed on the PBS. My children and I were with Health Minister Greg Hunt the day it was listed,” said Deborah.

“It’s so important that patients can get this treatment. I still think it is the most powerful drug we have in our arsenal (apart from CAR T-cell therapy),” said Deborah.

“I’d like to see venetoclax/obinutuzumab front line.”

“And I’d really like to see the end of FCR*, which is chemotherapy, except for people with the right [genetic] markers to respond well to it, which is a very small proportion of CLL patients.

“I was one of the earliest people on venetoclax,” said Deborah, but some people had been on it since the first trial in 2011.

“Unfortunately, because of all the patient journalism I’ve ended up doing, when I went to an international conference for CLL in November 2017 in New York and saw Dr Mary Ann Anderson presenting her research, I discovered that resistance [to venetoclax] was developing in some of the early patients.”

Read an interview with Dr Mary Ann Anderson about the development of venetoclax in Australia

Deborah stayed on venetoclax for four years because she didn’t have any side effects and it wasn’t known what would happen if she stopped it.

“But the standard of care now is that you’re on venetoclax for two years,” explained Deborah.

“There’s a theory that because I stayed on drug for four years, maybe that’s why the resistance developed. Other people haven’t relapsed after the two years, and those who have relapsed have actually responded again to the drug when they’ve had it [again, after a break].

“I don’t want people to hear my story and go, ‘Oh, but I’m going to relapse’, because that’s not the case.

“I have very aggressive disease. I was already relapsed and refractory when I started it.

“I got one of the deepest remissions they’d seen on this treatment, and I got no detectable disease in the bone marrow for two years on it.

“Dr Piers Blombery and Dr Mary Ann Anderson have identified a gene that has developed in patients while they’ve been on venetoclax that has made their disease resistant to it.

“Basically, ventoclax turns off a pathway, and CLL is so smart it finds a way around that pathway to start growing again in some patients with aggressive disease.”

Deborah’s relapse and what happened next

When venetoclax stopped working for Deborah, she had a “very slow relapse”.

“We’re talking a tiny amount of disease. They were finding it at the molecular level, but knowing my disease doesn’t stay molecular very long–it really takes off–they were trying to find out how quickly it was progressing before deciding to switch treatments, because I had done so well on venetoclax,” said Deborah.

In February 2019, the decision was made for Deborah to try four cycles of rituximab (MabThera®), as an experiment, to see if that would help the venetoclax hold the line a bit longer.

“It wasn’t going to be a cure for me, but I was really running out of options as to what we’d do next.

“It gave me two months where the disease was knocked back a bit, but it was pretty unpleasant.

“It was the third time, I’d had a monoclonal antibody and I think I was starting to develop resistance to that. I struggled with a lot of pain. I’d had a nice easy ride on venetoclax and it was quite a shock having a treatment that was hurting me and causing all these side effects,” said Deborah.

“By August the CLL was really coming back and I was planning to go to the American Society of Hematology (ASH) conference in Orlando in the U.S. that December,” said Deborah who has been going to the European Hematology Association meetings, the International Workshop on CLL, and to ASH each year.

“I interview doctors from a patient perspective about scientific research and clinical trials, and tailor that information for Australians,” Deborah explained.

“The way I see it is… patients don’t have to read scientific papers, but they need to be aware of what science is doing because at some stage, especially with CLL, they are going to need the latest treatment.”

Joining the Blood Cancer Taskforce

Motivated by the lack of a standard of care practice for CLL and her annoyance at people not being referred on to clinical trials, Deborah accepted an invitation to join the Federal government’s Blood Cancer Taskforce in September 2019.

During a flight to Canberra to attend a Taskforce meeting, she sat next to Dr Michael Dickinson, a haematologist who specialised in aggressive lymphoma, who asked how she was going.

“I said I’d relapsed on venetoclax and all I really had left was a BTK inhibitor, that I could get ibrutinib on the PBS, but I’d much prefer acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib was in trials, and we’re discussing which one to put me on,” she said.

He asked if she knew of the CAR T-cell trial** that was opening soon at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and explained that, to qualify, trial participants had to have been on ibrutinib for six months. Deborah knew about this one-off treatment. She had met people who’d had the new form of immunotherapy in America and whose disease had not relapsed.

Then, in early-December last year, Deborah set off once again to the ASH conference in the U.S.

“I did all these interviews with CAR T experts including with Professor Tanya Siddiqi of the City of Hope National Medical Centre (California) and decided if I couldn’t get to the Peter Mac [trial] I would go to the City of Hope and have my CAR T-cell product there, although that was going to cost a million dollars, so I wasn’t sure how I was going to do that.”

Deborah doesn’t know why, but the decision was made to take her off venetoclax the week before she went to ASH.

“So I get to America and my disease is going off.

“My neck is suddenly swollen. I’ve got lymph nodes under my armpits. I’m actually panicking because I was not expecting to get bulky disease immediately,” she said.

“It’s not something you see when you come off venetoclax, so my disease obviously decided it’d had enough.

“But luckily I’m with every great haematologist in the world and I’m interviewing them.”

“I said to [Professor] Miles Prince, ‘before we do the interview, can you just feel my neck, tell me what you think?’, and he’s like, ‘you’ve definitely got some lymphadenopathy but I don’t know what your neck was like before, I’m not the person to ask’.

“Basically, I got 40 opinions at this conference,” said Deborah.

When she returned to Australia, she spoke to her lead haematologist, Professor Con Tam, and although he wasn’t sure if she’d get on the CAR T-cell trial in Australia, he put her on ibrutinib in January this year.

“I didn’t tolerate it as well as I had venetoclax. I had quite a lot of side effects–joint pain, bruising–but it worked, and my disease started going back into remission.

“We got to June and, in the meantime, COVID happened and the CAR T-cell therapy trial had been put on hold.

“I asked about the CAR-T trial and Con checked with Michael.

“It had reopened, and Con said, ‘let’s get you on it’, so screening [a bone marrow biopsy, CT scan, ECG, and bloods] was booked for the day after I’d been on ibrutinib for six months!

“And the way the trial works is that they do the leukapheresis [the T-cell harvest] before you even know if you’re on the trial.”

It’s a three-hour process that involved “a massive needle” and an anti-blood clotting drug that made Deborah vomit.

“I thought… I’ve got stable disease, I could have had years of ibrutinib, what am I doing?

“Anyway, it just happened really quickly.”

Deborah’s T-cells were sent to America to be re-engineered, but there was a hold-up due to COVID, and she waited seven weeks for them to be returned.

This meant she needed another round of screening to provide a new baseline for the trial.

“It showed very little detectable disease and the CT scan was clear. I was very well,” said Deborah who at the time was having “major second thoughts”.

“I could not get my head around what I was doing.”

The anguish of having CAR T-cell therapy while well and healthy

“A private counsellor helped me reason that this was about long-term survival, rather than waiting for another drug to fail, then running out of treatment options, or having a bone marrow transplant as salvage therapy, which was the last thing I wanted to have.

“My mental anguish was about the decision to do something which could have killed me.

“Even though the doctors said, ‘you’ll be fine, you’ve got little disease, we’re not expecting you to have side effects, I’ve lost two friends within hours of having their CAR-T transfusion.

“They were very much like me, patient advocates campaigning for the best treatment, and they got those treatments first.”

On top of this, Deborah was getting a CAR T-cell product that was new.

“Anything new is scary, and you don’t really want to be the first patient having something. But equally, this was such an amazing opportunity for me. My disease was in its best state ever to have this. My doctors were confident it would work, and if it didn’t work, that it wouldn’t harm me.

“With CAR-T, it really does either work, or it doesn’t. And if it doesn’t, there’s a risk of mortality,” said Deborah.

“I’m on an international CAR-T patients Facebook group. There’s 2000 of us on it and every day you’re hearing great news from someone, then devastating news from someone else. It’s that black and white.

“What scared me was that first month after infusion; what I was going to go through? I was very scared about how sick I might get.

“It was the first time in 10 years of having this disease that I’ve done an advanced care directive and sorted my will out. I prepared everything in case I died.

“So mentally, to go into something where you really thought you might die, when you’re well, was incredibly difficult.

“I’ve always been a pioneer. I genuinely think it’s the bravest thing I’ve ever done, but I was worried that it was also the most reckless. I was very scared that I wasn’t being brave as much as reckless with my good health.

“But I’ve spent years making sure I’ve had the best doctors and I’ve trusted them. That’s always been my mantra to patients; find doctors you trust.”

Once Deborah’s cells had been re-engineered, she decided to go ahead with the procedure.

“This is a $600,000 treatment and I was getting it free, and a lot of people had gone to a lot of effort to make sure I got it.”

Three days after her T-cells arrived back in Australia, Deborah had three days of lympho-depleting chemotherapy, just enough to wipe out her immune system. After having the weekend to recover, Deborah went to the apheresis ward on a Tuesday.

“A nurse infused a vial of my engineered T-cells and that was it. It was so weird.”

“This was a really expensive, amazing product and thousands of people had been involved in getting it into me and this senior nurse just infused it, then did a flush, and that’s it.

“Then I spent three days just watching Netflix, and writing, and reading, and nothing at all happened to me,” said Deborah, and she went home on the Friday.

She was told that Day 11 was when they could expect to see some activity.

“But because I have CLL and very little disease they weren’t expecting much of a reaction and they certainly weren’t expecting something called cytokine release syndrome, which causes fever and can become serious.

“They know how to manage it better now, than when my friends died.”

On Day 10 Deborah started getting a “massive amount of pain” in her bones, “like someone was giving me a bone marrow biopsy all over my body”. The pain worsened, she started getting a fever and started shaking. When the fever spiked, she spent the night of Day 11 in the high dependency ward at Royal Melbourne Hospital and on Day 12 she was pleased to see the haematologist was Dr Mary Ann Anderson who until then she had admired but never met, and she was transferred back to the Peter Mac.

“She was pretty sure I had cytokine release syndrome,” said Deborah.

“They said I might have had more disease than they thought.”

Mild pain continued for another week.

“I swear I could feel the CAR T-cells going around my body mopping up the CLL cells.”

“I’d get a pain suddenly in my armpit, which was where my lymph nodes would always grow the most, and hang around there for the day, then it went up to my jaw, on to the lymph nodes in my face, and the back of neck, which was sore for a few hours.

“It was like going around, just cleaning out everything. It was incredibly exciting.”

Deborah doesn’t think CAR T-cell therapy should be a salvage or last-ditch treatment.

“I think if you’re as well as you can be going into it, the outcomes are better. That’s what I’ve found talking to CAR T-cell therapy doctors. Tanya Siddiqi, in particular, wants to see it become second line treatment.

“Patients like me put themselves on the line, not for unselfish reasons, but we’re the ones that are going to make it a lot easier for the patients in a few years’ time, like with me now saying, ‘I went around the world to get venetoclax and obinutuzumab’.

“There are so many really good trials out there that are better than standard of care and patients really need to ask their doctors about them.

“It’s really up to everyone to say, ‘are there any new treatments I should be aware of? Is there a clinical trial, even if it’s not in my state?’.”

You can read Deborah Henderson blog, abtandme.

* Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab

** An international trial, with four sites in the U.S. and one in Australia (at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre). The trial has three arms, for CLL, DLBCL, and ALL.

Last updated on April 5th, 2022

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.