Christine has a rare genetic predisposition to MDS

After losing her dad to MDS, and her brother’s diagnosis just a month before hers, Christine Heath’s family underwent genomic testing to understand whether their MDS could be hereditary.

Christine, a high school maths teacher, fell suddenly, back in 2015, when walking up the stairs to class, then fainted while lining her students up.

“It was just for a split second and I only dropped my books,” said the now 53-year-old from Port Lincoln, South Australia.

But she thought to herself, “that’s not right”, and went to the doctor to be checked out. Her blood tests returned some “funny results” and her doctor was particularly concerned about her haemoglobin level.

She was given the option of redoing the test in three months or going straight to a specialist.

“Given my dad, Geoff, had died from MDS in 2011, I opted to go to the specialist,” said Christine.

She saw the same haematologist who had treated her father, and he assured her any blood issues could not possibly be hereditary, that it was unlikely to be MDS, but he would monitor her over the coming years.

A ‘double-whammy’ diagnosis

After being closely monitored for several months, Christine was formally diagnosed in April 2016 with myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis (MDS/MPN-RS-T)*.

“This was just a month after my older brother, Stephen, who was also going to our dad’s haematologist, received the same diagnosis – a double whammy,” said Christine.

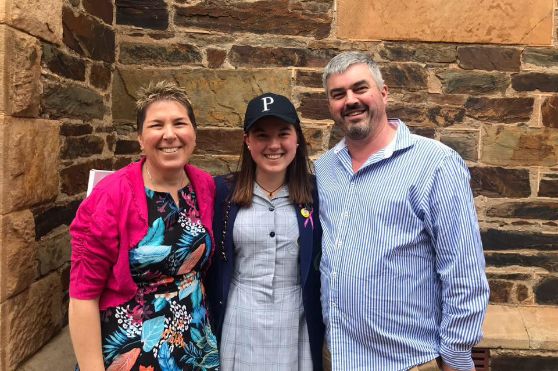

“My daughter, Ashleigh, was in year 10 at the time and I really wanted to be actively involved in her life, see her graduate, and live with my husband, Greg a lot longer.

“To begin with, I was put on ‘watch and wait’ with tissue and blood samples taken to find a stem cell donor.”

genomic testing

Even after her diagnosis, her haematologist was still reluctant to class her MDS as hereditary.

It wasn’t until Christine, Stephen, and their partners attended a Leukaemia Foundation MDS workshop in September 2016 that they started to find some answers.

“The workshop was in Adelaide and there was a geneticist there, Professor Hamish Scott, who we approached after his session, and told him about our situation,” said Christine.

“He said straight away, ‘oh I definitely want your genes… let us do some testing’.”

Another haematologist arranged for samples from Christine and Stephen to be shared with Prof. Scott and extra information about their dad and grandmother was provided.

The researchers asked her mum, Gill, for permission to use Christine’s dad’s blood samples. These had been stored as they looked different, but Geoff’s medical team was unable to understand why at the time.

“My mum also remembered that other family members had experienced blood issues and so they did a family tree and tracked it back a couple of generations,” explained Christine.

“It was then confirmed that we do indeed have a genetic predisposition to MDS!”

Read about the Blood Cancer Genomics Clinical Trial headed by Professor Hamish Scott in Adelaide and supported by the Leukaemia Foundation.

Ashleigh also has provided hair and blood samples, but she chose not to ask for information about any findings.

“She said she might when she has a family one day, but right now she’s focused on living for every day and doesn’t want that hanging over her head,” said Christine.

“She has just begun studying science at the University of Adelaide, majoring in immunology and genetics.

“We are really proud of her and the interest she has in the science behind all this. She could be the one who makes a difference for us in the future.”

Navigating treatment

In October 2016, Christine flew to the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne to get a second opinion.

“I learnt there that there were no clinical trials suitable for me and to just continue to maintain a balanced diet and consider part-time work.”

Early the following year, Christine needed to begin having blood transfusions and erythropoietin (EPO) injections every two months.

In 2018, as her condition worsened, she stopped work altogether.

“I’ve been on income protection ever since,” she said.

“I strongly encourage people to check whether their super gives them the option.”

Time for transplant

After living with Ashleigh in Adelaide for 12 years while she completed her schooling, Christine moved back to Port Lincoln to be with her husband in early-2019. Greg had stayed at Port Lincoln to support his parents as his father was battling leukaemia at the time.

When Christine’s transfusions got closer and closer together, her haematologist said, ‘time’s up, we’re going to transplant’.

“A sudden drop in two of the blood lines had appeared, which was the marker he was waiting for,” she said.

“I was a bit scared, but I knew that’s what I wanted to do.

“I felt far too young to die and I didn’t want to have to deteriorate like my dad had done before he passed.”

Ashleigh had produced a booklet for her senior school research project on the associated benefits and risks of transplants.

“Her project question was, ‘do the positive outcomes of getting a stem cell transplant to treat blood cancer outweigh the risk factors?’” said Christine.

“She interviewed a number of haematologists, ran a patient survey, and did a heap of research.

“She did an amazing job, and I think it really helped her to understand the process and cope with what I was going through.”

Christine and her family were given the time to take a holiday together before her transplant.

“We went up to Queensland and did ‘the worlds’,” said Christine.

“We were able to visit Ashleigh’s cousins there, and I didn’t want to take the risk of going overseas in case something went wrong.

“It was such a great trip. I’m not a big ride person but I was chief bag holder and took all the photos while they went on the rides.”

On 16 August 2019, Christine had her transplant with stem cells donated from the umbilical cord blood of two baby girls, after a previous donor match was no longer viable due to age.

“When I got to the hospital everything happened very quickly. I was started on chemotherapy and then I had full body radiation.

“On transplant day, I had Greg and my mum there, as well as Stephen and his wife, as he was about to have his own transplant and wanted to see the whole process.

“My niece, Stephen’s daughter, was also there. She had just finished her honours degree in science, supervised by haematologist, Dr David Yeung.

“Shortly after, she was employed to work with the transplant team doing all the data collection for transplant patients and looking for trends in treatment.

“It was feeling a little bit like a party, but it was kind of a letdown as the transplant itself is like having a transfusion.”

Christine needed to stay in hospital for seven weeks after the transplant.

“I consider myself extremely lucky as I didn’t have any long-term issues with graft versus host disease (GVHD) and didn’t go into intensive care once,” she said.

“I did go off my food for a bit and had to have a feeding tube, which I hated. I had a bad reaction to cyclosporine**, and they put me on steroids for suspected GVHD which caused me to develop steroid-induced diabetes.

“That was only temporary for about three months and by the time they had taught me to do the injections myself, it was time to stop.”

Leukaemia Foundation support

Leukaemia Foundation support

Christine and Greg stayed at the Leukaemia Foundation patient and family accommodation village in Adelaide for six months during her transplant and recovery.

“It was really important to stay close to the hospital as Port Lincoln is a seven-hour drive from Adelaide,” said Christine.

“We loved it there and we made quite a few friends around the village. We all kept an eye out for each other.

“There’s morning teas and the staff put on a Christmas lunch for everyone. There’s also a nice little games room where my husband and I would play a bit of ping pong or table tennis when I was feeling better.

“I cannot thank everyone from the Leukaemia Foundation enough – they were brilliant.”

Christine was kept busy during her recovery, with regular appointments and blood tests.

“These were weekly to begin with, then steadily decreased to fortnightly and monthly appointments,” said Christine.

“I also had lots of physio to build my muscle as I had lost about 15 kilos while in hospital.”

Although the Heaths had hoped to return home in February 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak meant they had to remain in Adelaide until the situation stabilised.

“I actually think I would’ve struggled being away from a major hospital during that time. You want that peace-of-mind that help is just down the road should you need it,” she said.

Focused on the future

Eventually returning to Port Lincoln in April 2020, Christine has been focusing on slowly settling back into everyday life.

“Life is looking really good and I’m now even talking about when I can return to work,” she said.

“I try to exercise every day and do what housework I can. I keep busy with people dropping in, and I’m really looking forward to summer so I can get back to the beach.

“But I’m always conscious of not overdoing it as I can still get really tired some days.”

Christine has regular tele-health appointments with her haematologist and travels back to Adelaide every two months for a face-to-face check-up.

“I can have my blood tests in Port Lincoln and I need to have a venesection fortnightly because my iron levels are too high from all the transfusions,” explained Christine.

“I also have an immunoglobulin infusion once a week which is a subcutaneous injection, two little needles into my stomach which I’ve been taught to self-administer.”

Now she is firmly focused on living for every day and is confident that with medical advancements, outcomes for people with genetic diseases will improve.

“I’m still in contact with Prof. Scott and serve as a consumer advocate whenever the opportunity arises,” said Christine, who together with two other women, started an MDS/MPN-RS-T Facebook support group.

“I also want to stress that our family is an extremely rare case and MDS is not typically a hereditary disease,” said Christine.

*MDS/MPN-RS-T is a rare subtype of MDS/MPN characterised by anaemia, bone marrow dysplasia with ring sideroblasts and persistent thrombocytosis ≥450 × 109/L with proliferation of large and morphologically atypical megakaryocytes.

**Cyclosporine is an immunosuppressant used to prevent rejection, following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.

Last updated on February 22nd, 2022

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.

Leukaemia Foundation support

Leukaemia Foundation support