What is a stem cell transplant?

A bone marrow or blood stem cell transplant is a treatment that restores stem cells after high dose chemotherapy. People with certain types of blood cancer can have a stem cell transplant. The are also certain non-haematological diseases treated with a stem cell transplant.

Blood cancers that can be treated with a stem cell transplant are:

Stem cells are the baby cells of the bone marrow. They divide and grow into different types of blood cells. The different types of blood cells are:

- White blood cells – are part of your immune system. They protect your body from infection and disease.

- Red blood cells – carry oxygen and nutrients throughout your body

- Platelets – help the blood clot and prevent bleeding

A stem cell transplant ensures that the bone marrow is repopulated with healthy blood stem cells. This is after high-dose chemotherapy and sometimes radiotherapy. The new blood stem cells rebuild your body’s blood and immune systems. A stem cell transplant is one part of a treatment plan. In some treatment plans transplant is the last step. In others, blood cancer treatment may be required after transplant to maintain disease control.

Types of stem cell transplants

A stem cell transplant involves receiving healthy blood stem cells through a line into a vein. There are several terms used to describe a stem cell transplant. This depends on where the stem cells are collected from:

- Peripheral blood – a peripheral blood stem cell transplant

- Bone marrow – a bone marrow transplant

- Umbilical cord blood – a cord blood transplant

Once the stem cells enter the blood stream, they travel to the bone marrow. In the bone marrow they start to grow, divide, and mature into healthy blood cells. This is called engraftment.

There are two main types of transplants:

- An autologous stem cell transplant – your own stem cells are collected and then given back to you after high dose chemotherapy.

- An allogeneic stem cell transplant – you receive stem cells from a donor, often a blood relative.

The type of transplant you have depends on several factors, including:

- The type of disease you have

- Your age

- General health

- The condition of your bone marrow

- Whether you would benefit from receiving donated stem cells. Or if your own stem cells can be used.

Autologous stem cell transplant

Autologous transplants are used to treat blood cancers like lymphoma and myeloma. An autologous stem cell transplant means that you receive your own stem cells. They allow the use of high dose chemo to treat your blood cancer.

In an autologous stem cell transplant your stem cells are:

- Collected while you are in remission or have minimal disease.

- Frozen (cryopreserved) until after your blood cancer is treated with high dose chemo.

- Defrosted and given to you through a line into your vein.

An autologous stem cell transplant can provide some patients with a better chance of cure or long-term control of their disease. Most people have a single autologous stem cell transplant. Others, like people with myeloma, may have two or more transplants.

Planning your autologous transplant

Your treatment team will normally give you timeframe of when you might have your transplant. The time you spend in hospital will vary based on the type of transplant you have. It can take about three to six months to recover from an autologous stem cell transplant.

It is important to be as prepared as possible for your transplant. This is a list of things to consider before you begin:

- A carer – you will need somebody to help support you through the transplant and beyond

- Organise your financial affairs

- Make a Will and organise a Power of Attorney

- Consider organising your leave entitlements from work, study or school

- Look into Centrelink and health insurance benefits

- Organise childcare

- Delegate a ‘point of contact’ in your family or close circle so that they can provide updates to everyone.

Pre-transplant ‘work-up’

You will have many tests and procedures in the weeks leading up to your transplant. This is to check your overall health and prepare for the transplant.

Tests and procedures likely to be done:

- Chest x-ray

- Heart function tests

- CT and PET scans

- Lung function tests

- Eye tests

- Bone density scan

- Urine testing

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Blood tests including screening for infections

- Dental checkups

- Central venous access device (CVAD) insertion

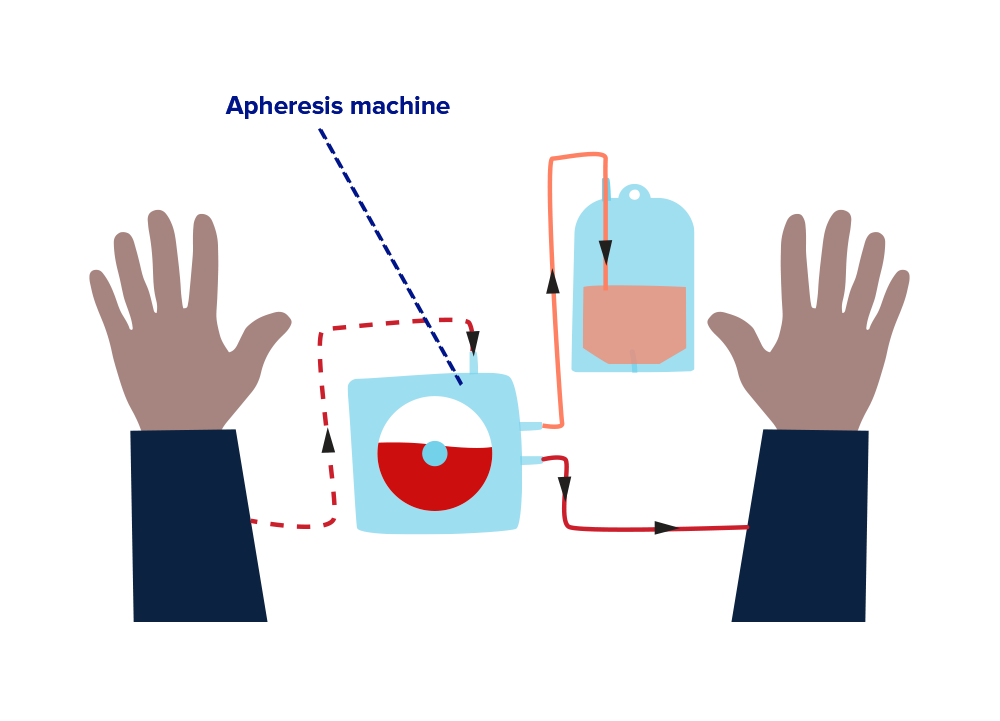

Autologous stem cell collection

Your treatment team will plan the timing of your stem cell collection. This is also called stem cell harvesting. You will have an injection to help the stem cells move from your bone marrow into your blood. This is so the stem cells can be collected from your blood through a vein. The process for collecting stem cells is called apheresis. Your blood passes through an apheresis machine. The stem cells are separated from your blood and collected into a bag. The rest of your blood is returned to you. The stem cells are then frozen until they are reinfused.

Conditioning treatment

Conditioning treatment is given to you in the days before your stem cell reinfusion. This includes high dose chemotherapy, and sometimes immunotherapy and radiation therapy. The aim is to kill any remaining blood cancer cells. It also makes room in the bone marrow for the new healthy stem cells. You will have some treatment side effects which may include:

- Low blood cell counts

- Fever and infection

- Bruising/bleeding

- Nausea and vomiting

- Mouth ulcers

- Changes in taste and smell

- Bowel changes

- Skin changes

- Tiredness

- Hair loss

- Weight loss/gain

The transplant (Day 0)

Day 0 (zero) is the day of your transplant, or stem cell reinfusion. Your collected frozen stem cells are defrosted and re-infused through a vein, or your CVAD. It is a short procedure, like a blood or platelet transfusion. Your reinfusion will be in a hospital either in a day infusion unit or an inpatient ward. The number of stem cells re-infused depends on the amount collected. Some of your stem cells may remain frozen if another transplant is planned.

Pre-engraftment

Your reinfused stem cells travel through the blood and into the bone marrow. In the bone marrow these stem cells produce all types of blood cells. This is called engraftment. Engraftment happens about 10-28 days after your stem cells are infused.

You will be monitored closely including regular blood tests while you wait engraftment. It is likely you will be an inpatient when your white blood cell and platelet counts are at their lowest. This period is called the nadir, you will be at high risk of:

- Developing an infection

- Unexpected bleeding

- Side effects from conditioning chemotherapy

Precautions to take:

- Protect yourself from infection

- Protect yourself from cuts, grazes, and bruises

- Discuss side effects and how to manage them with your treatment team.

Infections when your white blood cells are low are serious. They need to be treated with antibiotics as soon as possible. You will also have an injection under the skin (subcutaneous) to help increase your white blood cells (neutrophils). You may need a platelet or blood transfusion to reduce the risk of bleeding and help with fatigue.

Leaving hospital

Recovering from a stem cell transplant takes time. Your blood counts will start to increase, and your side effects will improve. Your treatment team will assess if you can be discharged from hospital. This includes review of your blood counts and your physical condition. You will need to visit the day unit at the hospital. You will have a blood test and review with your treatment team to see how you are progressing. Your immune system will gradually improve. But you should continue to take precautions to prevent infections. Things you can do to prevent infection:

- Regular hand washing

- Daily showering

- Regular mouth care

- Avoid people with suspected colds, flu and other viruses

- Avoid close contacts and people with chicken pox, measles or other viruses

- Avoid people who have had a live vaccine such as polio

- Avoid places with large numbers of people

- Wear a mask

- Avoiding garden soil and potting mix

- Wash your hands after handling animals and avoid cleaning up their waste

- Avoid activities that damage your skin or wear protective clothing.

It takes about three to six months to recover from an autologous stem cell transplant. It is important to focus on activities to help your physical and emotional recovery. Living well with blood cancer has practical tips and resources.

For further information read our booklet Autologous stem cell transplants – A guide for patients and their support people.

Allogeneic stem cell transplant

An allogeneic stem cell transplant means that you receive stem cells from a donor. Allogeneic transplants are used to treat some blood cancers. These include certain types of leukaemia, and some myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative neoplasms. Often a blood relative is a donor, they may be a full or half genetic match to you. If no blood relatives match, then a match unrelated stem cell donor may be found on the Australian and overseas donor registries.

In an allogeneic transplant:

- The donor’s healthy stem cells are used to replace your diseased cells.

- Very high doses of chemotherapy are given to empty the diseased bone marrow. This is replaced by the healthy donor stem cells.

- The donor stem cells should mature, attack, and destroy any diseased cells left in the patient’s body. This effect is called graft-versus-tumour.

Planning for your allogeneic transplant

Your treatment team will give you a timeframe of when you might have your transplant. During your transplant you will be in hospital for three to six weeks, sometimes longer. You will need to stay near the hospital for at least 100 days after the transplant. This is for regular checkups and to manage any complications. During this time, you and your carer will need to relocate close to the hospital if you are from a regional or remote area.

Find out more information about Leukaemia Foundation accommodation.

It is important to be as prepared as possible for your transplant. This is a list of things to consider:

- A carer – you will need somebody to help support you through the transplant and beyond

- Organise your financial affairs

- Make a Will and organise a Power of Attorney

- Consider organising your leave entitlements from work, study or school

- Look into Centrelink and health insurance benefits

- Organise childcare

- Delegate a ‘point of contact’ in your family or close circle so that they can provide updates to everyone.

Getting your affairs in order has information to guide you. Or contact our Leukaemia Foundation Health Care Professionals on 1800 620 420.

Donor search and match

Your treatment team will coordinate a donor search for your allogeneic transplant.

This could include:

- Discussing stem cell donation with blood relatives

- Performing an unrelated donor search

Some possible donor matches are:

- HLA matched donor – HLA stands for human leukocyte antigen. It is protein on the surface of the body’s cells. Your blood is tested for its HLA markers. It is then compared to a donor’s blood for a HLA match. The aim of HLA matching is to find a donor with similar HLA markers on their cells. The donor could be a blood relative, usually a sibling. Or a match unrelated donor found on a donor registry.

- Mismatched unrelated donor – Sometimes the only available donor is an unrelated mismatch. This means the unrelated donor’s HLA markers partly match yours.

- Haploidentical donor – A haploidentical donor is a half match. Their HLA markers are a half match with yours. This is a blood relative, usually a parent, sibling, or sometimes a child.

- Cord blood donor – Cord blood is collected from the umbilical cord when a baby is born. It is HLA tested, then frozen and stored. As the cord blood donor’s immune system is very immature the transplanted cells do not have to be an exact match. An adult may need two cord blood donor’s due to the small number of stem cells in a cord blood donation.

Pre-transplant workup

You will have many tests and procedures in the weeks leading up to your transplant. This is to check your overall health and prepare for the transplant.

Tests and procedures likely to be done:

- Chest x-ray

- Heart function tests

- CT and PET scans

- Lung function tests

- Eye tests

- Bone density scan

- Urine testing

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Blood tests including screening for infections

- Dental checkups

- Central venous access device (CVAD) insertion

- Dental checkups

Your treatment team will talk about a transplant protocol with you. This covers the timing of treatment. It includes the treatment plan for the days before and after your stem cell infusion. The transplant protocol includes:

- Pre-transplant – the conditioning chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy

- Day 0 – the day you receive your stem cells

- Post transplant – monitoring for engraftment (when the stem cells produce new blood cells)

Donor stem cell collection

When the donor stem cells are collected depends on the source of stem cells. It also depends on the location of the donor, who may live overseas.

- Blood stem cells – collected from the donor through a peripheral blood stem cell collection. The donors’ blood is taken from a vein in their arm. The blood goes through an apheresis machine that takes out the stem cells. The rest of their blood is returned through another vein. The stem cells may be infused soon after collection or frozen.

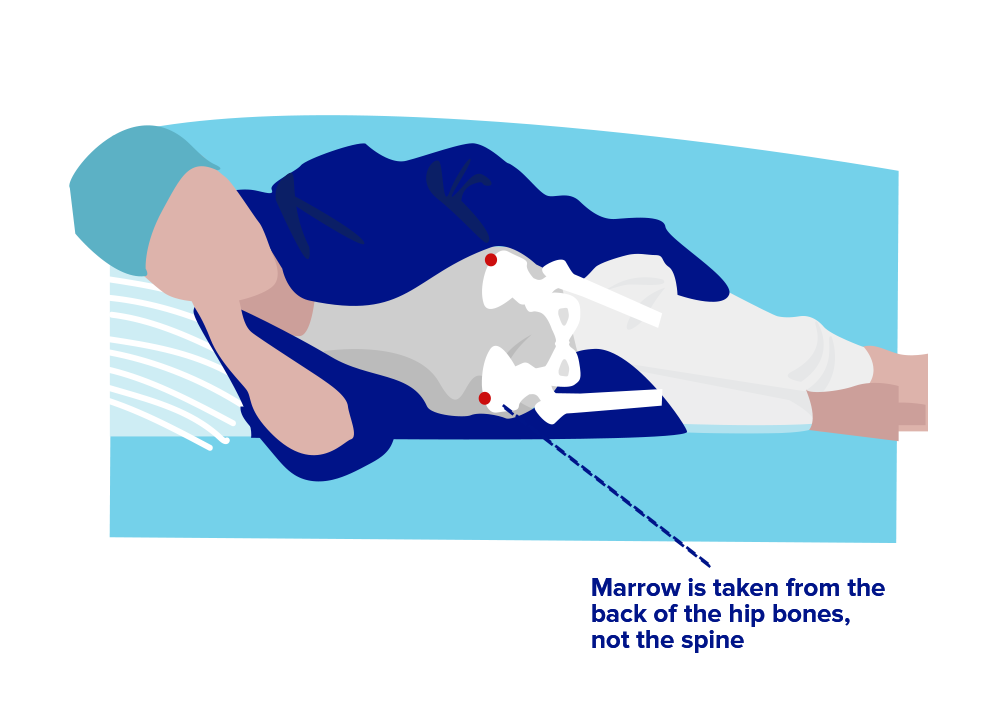

- Bone marrow stem cells – collected in an operating room while the donor is anesthetised. The stem cells are collected through needles inserted into the bone. The stem cells may be infused soon after collection or frozen.

- Cord blood stem cells – cord blood is collected from the umbilical cord when a baby is born. It is frozen and thawed for infusion.

Find out more information for relative donors and registered stem cell donors.

Conditioning chemotherapy

Before your transplant you will have several days of treatment. This includes high dose chemotherapy and sometimes immunotherapy and radiation therapy. The type of conditioning treatment depends on your donor match, type of blood cancer and you overall health. The aim of conditioning treatment is:

- To treat the blood cancer

- Make room in the bone marrow for the transplanted stem cells

- Weaken your immune system so the donor cells aren’t rejected

You will have treatment side effects which may include:

- Low blood cell counts

- Fever and infection

- Bruising/bleeding

- Nausea and vomiting

- Mouth ulcers

- Changes in taste and smell

- Bowel changes (diarrhoea)

- Skin changes (rashes)

- Tiredness

- Hair loss

- Weight loss/gain

It’s important to let your treatment team know about any side effects. There are strategies and medications to help manage them.

Reduced intensity conditioning treatment – is lower doses of chemotherapy and radiation therapy. This means the side effects from the treatment may be less. It is used if you are older and have other conditions like heart, lung, liver or kidney problems.

The Transplant – Stem cell infusion

The day you have your stem cells infused is known as Day 0. If the stem cells are frozen they are defrosted at the bedside. They are infused into you through a vein, usually through your CVAD. The infusion is similar to a blood transfusion. This can take between thirty minutes to four hours.

If the stem cells have been frozen, you may notice an unusual smell. This smell may resemble garlic, asparagus or sweet corn, and last up to twenty-four hours after the infusion. You may also have a strange taste in your mouth. These effects are due to a preservative used in the freezing process.

Pre-engraftment

The stem cells find their way to the bone marrow. They start to mature into white blood cells, platelets and red cells. This is called engraftment. It usually takes ten to 28 days, depending on the type of transplant you have. You will be monitored closely including regular blood tests while you wait engraftment. When your white blood cell and platelet counts are at their lowest. This period is called the nadir, you will be at high risk of:

- Developing an infection

- Unexpected bleeding

- Side effects from conditioning treatment

During this phase you may need:

- Blood transfusions

- Antibiotics

- Intravenous fluids

Potential post-transplant complications

It is likely you will experience some post-transplant complications. These are often because of your conditioning treatment. You may have one or more at the same time. Post-transplant complications can occur any time during and after your transplant.

There are three common complications of allogeneic transplant:

- Infections – are common, they happen because the conditioning treatment destroyed all your good white blood cells. These normally protect us from infection. If you develop a fever or infection you will be given antibiotics.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) – is a virus that in a healthy person would cause flu like symptoms. When your immune system is weak CMV can cause a serious infection in any organ in your body. If a CMV infection does develop it is usually treated with intravenous antiviral medications.

- Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) – is a common complication of an allogeneic transplant. It occurs when the donated cells see your organs and tissues as unfamiliar cells that need to be destroyed. Most cases are mild or moderate and resolve over time with minor treatment. There is more information on our GvHD fact sheet.

Leaving hospital

Recovering from a stem cell transplant takes time. Your blood counts will start to increase, and your side effects will improve. Your treatment team will assess if you can be discharged from hospital. This includes review of your blood counts and your physical condition. You will need to visit the day unit at the hospital every day. You will have a blood test and review with your treatment team to see how you are progressing. You will be closely monitored for up to 3 months post-transplant. This is commonly mentioned as day 100.

Your immune system will gradually improve. But you should continue to take precautions to prevent infections. Things you can do to prevent infection:

- Regular hand washing

- Daily showering

- Regular mouth care

- Avoid people with suspected colds, flu and other viruses

- Avoid close contacts and people with chicken pox, measles or other viruses

- Avoid people who have had a live vaccine such as polio

- Avoid places with large numbers of people

- Wear a mask

- Avoiding garden soil and potting mix

- Wash your hands after handling animals and avoid cleaning up their waste

- Avoid activities that damage your skin or wear protective clothing.

It can take 12 to 18 months, or more, to recover from an allogeneic stem cell transplant. It is important to focus on activities to help your physical and emotional recovery. Living well with blood cancer has practical tips and resources.

Post transplant care

You will have regular visits to the hospital for post-transplant review. Your treatment team will assess your physical and mental well-being. Many side effects of a stem cell transplant last for a short time. Some can persist for months and occasionally years after the transplant.

Post transplant care includes:

- Monitoring and managing late effects.

- Vaccinations – after an allogeneic transplant you lose the immunity to many of the diseases you were vaccinated against as a child.

- Screening for other medical conditions – like other cancers and heart disease.

- Lifestyle information – like wearing sunscreen and exercising.

For further information read our booklet Allogeneic stem cell transplants – A guide for patients and their support people.

References

Related stories

Last updated on March 3rd, 2025

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.