Terry’s ups and downs during 20 years living with CML

“It’s been so long, it’s hard to remember anything different” said Terry Robson-Petch.

This article contains themes of fatigue, long-term side effects, and mental health impacts

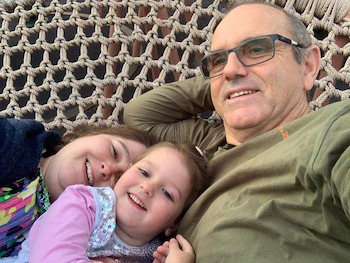

Diagnosed at 36, when he was a competitive wave ski surfer living on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, Terry is 56 now, he has a new partner, a five-year old, and they live in Brisbane.

“It’s hard to say how my life would’ve gone without CML. It might be very different, but you just can’t go back.

“The side effects I had from interferon certainly set in motion a bunch of things that probably wouldn’t have happened without it,” said Terry, referring to his mental health issues, marriage breakdown, and business failure.

“Everything that happened was incredibly hard and stressful. It changed everything for me and the people around me.”

But these days he’s says, “I’m certainly in a lot better place”.

Terry’s diagnosis with CML and treatment

Prior to his diagnosis in 2001, Terry had lost a lot of weight and was regularly throwing up, then he started getting “massive bruises, the size of a dinner plate”.

“At the time I was doing a lot of sport, so I blamed that, but the turning point was when I started to go that really sickly, jaundice-type colour. Once that happened. I was just like, ‘there’s something not right’,” he said.

“I did the usual male thing of, ‘it’ll be okay, it’ll go away’, until it didn’t, and I finally went to the doctor’s.”

Terry was sent off for an ultrasound to check on his spleen, and a blood test which indicated “there was something not right”.

“So I went off to see an oncologist who did a bone marrow biopsy to see what was going on and that’s when the CML diagnosis was reached.”

Terry’s initial reaction to his diagnosis was “confusing, because when somebody says ‘leukaemia’ you think of young children, not adults, so it was, ‘how can I have leukaemia?’”.

He was advised to take six months off work, “but I was running my own business building and selling watercraft – kayaks, canoes and wave skis”, said Terry who also competed “a lot on a wave ski”.

“I was in the hospital for a few days trying to get my white blood cell level down and to decrease the size of my spleen which was huge.

“They did a thing called leukapheresis on me, which is basically pulling the blood out of one arm, spinning off the white blood cells and putting the blood back in the other arm,” explained Terry, who went back to work a week later.

He’d been told he’d possibly live for another 10 years but that prognosis wasn’t a given.

“They put me on interferon pretty much straight away. That was the days before all the modern drugs,” said Terry, whose other option was having a bone marrow transplant.

“I didn’t handle interferon very well. It was a terrible drug in my books, and I would never take it again.

“It was the trigger, and everything went wrong after that. It started a cascading effect, which was hard to stop. Eventually my business collapsed, my marriage collapsed, everything.

“I had a pretty serious mental health reaction to the drug itself – a bipolar reaction, which apparently has happened to other people but it’s rare,” said Terry who had never had a reaction like that prior to or since being on interferon.

“I had a very major high and a very major low over about a six-month period.”

“So I took myself off it [interferon] and refused to take it because when I was high, I believed that everybody was trying to kill me and that there was nothing wrong with me,” he said.

“I managed to keep myself going by eating extremely well and exercising a lot, and my blood cell counts weren’t too bad for about six months.

“It was after I hit the depression stage, when I ended up in hospital for a week – I was suicidal at that point – that they did tests on me and another bone marrow biopsy to see what my levels were,” said Terry.

“That’s when I started to look at treatment options, and when I got lined up for a bone marrow transplant,” said Terry, and three unrelated donors had been identified as matches.

“I didn’t like the odds for a transplant. At the time, it was a 15% mortality rate, which I wasn’t too happy about, and a 50% chance that if it didn’t kill me, I would have some sort of ongoing complication for the rest of my life.

“I figured at best I had a third of a chance I’d be okay, which didn’t sound very good odds to me,” said Terry.

Then, two weeks before he was due to have a transplant, Terry was offered a new targeted therapy; the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), imatinib (Glivec®).

“That’s when Glivec first became available on the PBS, so I went on that and had a lot of success with it,” said Terry.

For the next 10 years, he took his tablet once a day along with medication to counteract the side effects which affected his stomach.

Then, about 10 years ago, when the imatinib “wasn’t being quite as effective” and his number of leukaemic cells was increasing slightly, he tried the second-generation TKI, nilotinib (Tasigna®) “and that seemed to settle everything back down again”.

At first, Terry was treated in Brisbane and he went back to the hospital there for a while but “it didn’t go particularly well,” said Terry.

“So I came back to my original oncologist who’s on the Sunshine Coast.

“I’ve basically seen her pretty much the whole time,” said Terry, and his appointments to monitor his CML are every six months.

“Thankfully these days it’s just a blood test. That’s been a real breakthrough in my books. For many years, it was a bone marrow biopsy, so I’ve had countless amounts of those. They’re not pleasant.”

When Terry first started on the nilotinib medication, which is two tablets twice a day, the side effects he noticed “pretty much straight away” were a change in his skin and he urinated a lot.

“I had these weird, lumpy horrible looking things on my arms mostly and my arms went really wrinkly really quickly. They looked like 70-year-old arms.

“But the main side effect “without a doubt” is fatigue. I do my best to push through it.

“Exercise helps but it can be difficult. You don’t really feel like exercising because you feel so bad, but if you do exercise it certainly helps, although it takes a long time and there’s a lag between when you first start, to where you actually get fit,” explained Terry.

“Some days by three in the afternoon I crash on the couch, and I can’t stay awake because I’m just so exhausted. But then after a bit of a break, I’ll jump back up and I’m off again, or try to.”

Surviving 10 years, then 20 years, and Terry still has a sense of “now what?”

Terry hadn’t thought about it beforehand but once he hit the 10-year mark, following his diagnosis, he was struck by a feeling of, “okay, now what?”.

“So now it’s 20 years, and I guess I’m still at ‘now what’ but not as bad.”

“Certainly, I’m fairly positive these days about going forward, but still slightly concerned about what this means to be on these drug treatments long-term because we’re the ones who have been on them for the longest period of time.”

Being unsure of the long-term prospects, Terry said, “the best way to describe it is – you’ve got that cloud over your head, as far as you’ve got an illness and what that means”.

“We don’t really know what that means other than being told by the doctors that we’ll probably die from something else.”

And this means living with and managing the side effects. If Terry feels sick, he is immediately concerned.

“I can’t help it but think the worst thing… ‘no, something’s wrong. The drugs aren’t working anymore’,” he said.

“It could just be a cold, or I just have a bad day and it’s just like, ‘no, what’s going on?’

“But that normally settles down fairly quickly once I go back to see the doctor, and six months later everything’s okay, and it’s just like, ‘okay, I’m still good’.

“And I’m slightly concerned that things aren’t going to keep going well; keep going the way they’re going.

“But so far the treatments keep working and I’m reasonably healthy other than the side effects.”

CML is not well understood

According to Terry, “people just don’t have much of an understanding” about CML, so he doesn’t tend to tell anybody he has this form of blood cancer, “especially people I’ve only first met”.

“I’m working for somebody one day a week as a push-bike mechanic and I haven’t told him because I don’t want him to think I can’t do the job,” he explained.

“It’s easy to not say anything because, if you do, they don’t understand what you are talking about.

“They look at me and go, ‘yeah, but you look alright’. That’s usually what people say, ‘you look fine’.”

“Most of my close friends know, but other than that I don’t overly advertise it.

“I don’t think my parents understand that well, and the last person that spoke to me about it said, ‘that thing you used to have, that’s all good now, isn’t it?’. That was their understanding!

“And when somebody mentioned issues they were having and I told them, ‘it’s been 20 years for me like this’, they immediately turned around and said, ‘well, you’re here’. Their understanding of it was, ‘well, you’ve just climbed up a mountain on a mountain bike. I’m sure, you’re okay’.

“That is a reality in a way, I guess, but what they don’t see is me just completely exhausted for the rest of the day and falling asleep on the lounge at two or three in the afternoon because I just can’t stay awake any longer.

“I don’t help that because I try to convince myself that I’m fine and I just push on as hard as I can.

“There’s really no education for the general population about this disease and what it means,” said Terry who believes it’s thought of as two things.

“Leukaemia is for little kids, and for most cancers, if you look really sick, then you must be really sick. That’s my perception,” he said.

“I just don’t know whether people understand that it’s an ongoing treatment for the rest of my life. I’m not magically better.”

“And there are side effects that go with that. If I had no side effects, it would be just normal life, but with the side effects, it’s something that’s not really understood.

For example, Terry said, “my memory’s not the best these days either, whether it’s old age or the long-term drug treatment”.

Starting over

After everything in his life fell apart for Terry, “I started over basically,” he said. He’s done different things workwise since then and now he’s repairing and painting carbon fibre pushbike frames, “so all the high-end mountain bikes and road bikes that all the guys are using these days”.

“I mountain bike a lot instead of surfing because I’m living in Brisbane and mountain biking is an exercise that I can do that I enjoy and that works really well for me.

“And I’ve ended up with a new partner – that’s the big thing that’s changed more recently.”

“She’s wonderful and we’ve had a child. Ella was a surprise that’s for sure and she keeps me on my toes,” said Terry who has two other children, Katie, 26, and Beau, 24.

Terry is mostly a stay-at-home dad as his partner, Alison Ingram, works full-time.

Terry’s thoughts on treatment-free remission

While treatment-free remission (TFR) has been discussed with Terry, “my doctor’s not keen and my levels have never been that consistent and are normally point zero zero something”, he explained referring to the BCR-ABL1 level in his peripheral blood.

“I’ve had zero zero zero previously, but it never stays exactly at that. The next time, it might be just up a little bit and then I’ll slowly creep back down again.

“That’s why I’m concerned that treatment free remission wouldn’t work for me. I think I wouldn’t get a particularly good result, then I’d have to get back on the drugs again anyway,” he said.

“If I go off Tasigna even for two or three months, which has happened a couple of times when I went to a different doctor and they kept messing up the supply of my medication, I found that when I went back on it, I had… I wouldn’t have called it depression… more of a severe uncontrollable sadness.

“So I don’t like the idea of going off Tasigna because coming back on, I seem to react badly, and it takes a while to settle back down. It doesn’t seem to last too long but it’s not a pleasant experience.”

However, Terry said if he achieved undetectable BCR-ABL1 for at least two years, “I’d go, ‘yeah, let’s try this’”, so TFR is a possibility and he’ll speak to his doctor about it again the future.

Terry and the Leukaemia Foundation

When Terry was first diagnosed, he was given some information about CML from the Leukaemia Foundation – the original Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML) – A guide for people with CML and their support people booklet.

“It took a long time to sink in what it actually meant, I guess,” he said.

And, over the years, pre-COVID-19, Terry went to the Leukaemia Foundation’s coffee and chat CML support group which met regularly at a café in Brisbane.

“It was interesting for me because until that point I’d never met somebody else with CML, so I had no understanding of what that meant to somebody else,” he said.

“It was nice to have support around that and talking to other people and getting an understanding of what they go through, and that I’m not the only one that feels this way or goes through that sort of stuff, made me feel a bit less alone.”

Terry also joined the Leukaemia Foundation’s CML Network on Facebook back in 2016 when he started sharing some aspects of his CML journey with others within this members-only online community.

“I have a look regularly and talk to other people about how they’re going,” he said.

“If somebody says, ‘I’m feeling awful. I’ve just recently started [a TKI], I feel horrible, what’s going on?’, I’m likely to give a bit of a feedback and encouragement.”

In June 2021, he posted, “I just reached a big milestone. It’s been 20 years living with CML. I’ve had my ups and downs but I’m still here which back in 2001 was unlikely because the prognosis was not the same as today…. ”

“They’re still replying every now and then,” said Terry about the responses he’s received. He’s had 53 comments to this post, as recently as mid-February 2022, and his last reply to those comments was, “Great to hear from other people who have survived and are living with CML.”

And when Terry reads about others whose diagnosis was 18 or 25 years ago, he said, “that’s good for me as well… that I’m not the only one who’s been on this treatment for this amount of time”.

Terry’s advice to others

“Get the right people around you, get the right treatment, get the right advice, and get the right help that you need,” is how Terry summed up his advice to others.

From listening to other people with CML, Terry said, “side effects certainly seem to be real that’s for sure because it’s so consistent between all of us – we all seem to have something”.

“Get the right oncologist who’s going to look after you and monitor you carefully, and try to get them to give you the time to discuss side effects and have a proper look at that so they can help you.

“That’s the one area that’s lacking with my medical team,” said Terry.

“My doctor will look at my numbers and go, ‘this is great, you’re great. See you later’, and I’m like, ‘hang on, I feel terrible all the time’, and her response is, ‘yeah, no, you’re fine’.

“So don’t let them fob you off.”

And while Terry said his oncologist was “not the best at that” [side effects], he said “she’s very good at getting me the treatment I need, so I’ve settled for that”.

“I think her understanding of mental health issues is pretty limited and I think quite a few doctors would be the same.

“As far as my mental health was concerned, around the time my marriage broke down, when she didn’t really understand what I was going through and how serious it was, she said to me, ‘now don’t you go getting sad again’.

“I was just like, ‘what’s that supposed to mean?’, but that was her understanding of me having a major mental health issue. It was all ‘sad’.”

For mental health services, please visit MindSpot Clinic – Free Online Mental Health Support

Last updated on June 8th, 2022

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.