Expert Series: Dr Ilaria Pagani talks treatment-free remission in CML

For Dr Ilaria Pagani, who grew up in Corgeno in northern Italy, attending the world’s most important haematology conference in 2013 was the beginning of an adventure that changed her life.

“As the winner of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Abstract Achievement Award, I presented my work on minimal residual disease on chronic myeloid leukaemia, done in my laboratory in Italy,” explained the biomedical scientist who had completed her PhD in Molecular Biology and Oncology the previous year.

At the ASH annual conference, held in New Orleans (U.S.), Dr Pagani met Professor Timothy Hughes and Associate Professor David Ross, and later, she was invited to join Prof. Hughes’ laboratory at the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI) in Adelaide as a visiting postdoctoral researcher.

So, in 2014, Ilaria left Italy with a backpack, little money, and not much English.

She had first heard about leukaemia, at school when she was young.

“One day one of my school friends donated a pink card with one coin to everyone in the class. This was the last time I saw him. He had leukaemia. This moment stuck with me and moved me,” said Dr Pagani.

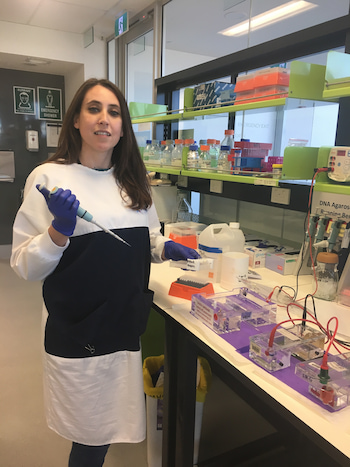

“It is an honour working with Prof. Hughes and alongside the world’s leaders in CML research,” said Dr Pagani, now a permanent Australian resident with an emerging international reputation in CML.

She specialised in medical genetics, completing her studies with honours in 2016.

Dr Pagani used her expertise in genetic diseases and DNA mutations to develop leading-edge technologies for studying mitochondrial DNA mutations and monitoring minimal residual disease (MRD) in CML patients.

In 2019, in a highly competitive global competition, she was awarded the inaugural international John Goldman Research Award for developing a predictive model of treatment-free remission (TFR) in CML. TFR refers to having a stable deep molecular response without the need for ongoing tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment.

Dr Pagani’s ground-breaking work clarified the identification of CML patients who may be able to achieve a deep remission, safely discontinue their TKI therapy, and therefore be considered cured.

Also that year, Ilaria received a prestigious Beat Cancer Project Mid-Career Research Fellowship from Cancer Council SA allowing her to further the understanding of the metabolism of CML stem cells.

She presented her original work, Mitochondrial DNA mutations are associated with response to imatinib in chronic myeloid leukaemia patient at the European Hematology Association Virtual Congress, in June, which was featured in the ‘Best of Theme’ section; the only CML research paper to achieve that honour.

CML and treatment-free remission

Dr Pagani describes chronic myeloid leukaemia as a rare blood cancer and an estimated 320 Australians receive this diagnosis each year.

CML affects the blood and bone marrow and is characterised by an overproduction of dysfunctional white cells, called granulocytes. The hallmark of CML is the Philadelphia chromosome, which carries the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene – the balanced reciprocal translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) between chromosomes 9 and 22. The protein BCR-ABL with deregulated tyrosine kinase activity guides an increase in leukaemic cells and their survival.

“CML is the only cancer currently cured through targeted therapy,” said Dr Pagani.

This treatment, with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, targets the BCR-ABL protein and has revolutionised the outcome for CML patients. Today more than 80% of these patients survive.

“Treatment-free remission is a new pathway to cure for CML patients.”

“About 25% of CML patients can achieve and maintain TFR for more than 10 years after stopping their TKI therapy,” she said.

“However, the many remaining patients need to take TKIs life-long, which can lead to an impaired quality of life, severe toxicities, a cumulative risk of organ damage including kidney, lung and heart function, and a substantial cost for the health system (about $40,000 per patient/per year).

“Additionally, about 20% of CML patients don’t respond to frontline therapy, and half of them tragically die due to disease progression or complications after a stem cell transplant.”

A CML patient member of the SAHMRI Myeloid Group, Lisa Mc Neil, who collaborates in Dr Pagani’s research projects, has been on TKI therapy for more than 12 years and she is concerned about her future.

“Since I found out from my doctor that TKIs have long-term side effects, including the vascular system, I have been worried that, even if the CML is under control, I have damaged my body,” said Lisa.

“I am now on a trial drug, called asciminib, which is apparently safer than the other TKIs for future vascular events, but my future is still uncertain due to the infancy of this drug.”

Dr Pagani worries that CML patients are told they will have a normal life span, and that CML is seen now as a ‘good cancer’ because they won’t die, “even though many still do”.

“It is often forgotten that most people with CML are living with this hanging over their heads, on a daily basis,” she said.

“It is always with them, with the constant reminders of fatigue, nausea, pain or other side effects.

“Some patients fast twice daily, before and after their medication, while others can’t work or can’t financially afford to have this disease.”

“We need to remember how far we have come, and not forget how far we have to go.”

“This is important with the number of CML patients increasing in the near future.”

Dr Pagani said more than 6,000 CML patients in Australia were dependent on lifelong TKI therapy.

“CML is set to become the most prevalent leukaemia by 2040 and, if no progress is made, an estimated three million CML patients will be dependent on TKIs globally.

“Increasing the number of patients who can safely cease TKIs and therefore be cured, is our priority.”

Clinical trials of treatment-free remission

The CML research group in Adelaide, which Dr Pagani joined in 2014, pioneered one of the world’s first trials of therapy cessation. The CML8 TWISTER study opened in 2006 and was led by A/Prof. David Ross and Prof. Timothy Hughes, and sponsored by the Australasian Leukaemia & Lymphoma Group.

Patients who enrolled in the study had exceptional responses to TKIs. They had to have been on imatinib treatment for at least three years and have undetectable BCR-ABL1 in the peripheral blood for at least two years.

“This study showed that 45% of these patients remained in treatment-free remission after therapy cessation without the need of treatment,” said Dr Pagani.

“The remaining patients relapsed, mainly within the first three to six months after stopping imatinib, with the latest relapse after 27 months. They restarted imatinib treatment and all regained an undetectable molecular response.”

In 2018, A/Prof Ross and Dr Pagani published the long-term results of this trial in the journal, Leukaemia. They showed that CML patients who achieved treatment-free remission could maintain it for more than 11 years and could therefore be considered cured.

“This was the first work showing the long-term safety and remarkable stability of response after imatinib discontinuation,” said Dr Pagani.

Since this first clinical trial of imatinib cessation, a growing body of TFR clinical trials has been developed around the world with imatinib and the newer TKIs, which has supported the safety and efficacy of this TFR approach. These trials, overall, show that about 50% of patients who cease therapy achieve treatment-free remission, while the other half relapse and need to restart their TKI therapy.

Dr Pagani said taking part in TFR can be a traumatic experience that may have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life. A recent global online survey involving over 1,000 patients across 68 countries indicated that 56% of patients felt a sense of fear and anxiety during the first six months after stopping their TKI.

According to Lisa McNeil, “patients are often hesitant to even try it as they feel they are doing well on their TKI, and they do not want to risk a possible relapse after cessation as this is an unknown when undertaking the option”.

It is still not known why, despite the exceptional response to TKIs prior to cessation, half of the patients relapse after stopping their TKI therapy while the other half are cured.

“The biological factors that determine successful treatment-free remission are poorly understood, and predictors of outcome after therapy cessation are not currently available in routine clinical practice,” said Dr Pagani.

Biomarkers of treatment-free remission

The most pressing priority for CML patients worldwide is, “what can be done to increase the rate of treatment free remission?”, said Dr Pagani.

The various TKI discontinuation trials have investigated a range of clinical and laboratory parameters for identifying key predictors of successful drug discontinuation. These include sex, age, depth of molecular response, BCR-ABL1 transcript type (e13a2 vs e14a2), pre-TKI interferon treatment, type of TKI, clinical prognostic scores (such as the Sokal index), early molecular response, time to deep molecular response, duration of deep molecular response, total TKI exposure, and immunological parameters.

“Only a few variables have demonstrated consistency in predicting sustained treatment-free remission,” said Dr Pagani.

“The total duration of TKI therapy and deep molecular response prior to stopping TKI therapy are perhaps the most consistently reported predictive factor for achieving treatment-free remission.”

An interim analysis of the EuroSKI study reported that each additional year of deep molecular response on imatinib prior to discontinuation was associated with a 2-3% absolute increase in the probability of treatment-free remission at six months following TKI cessation.

However, none of these predictive factors, called ‘biomarkers’, are used in the routine clinical practice. Clinical guidelines regarding the when and if of stopping TKIs are therefore a necessity for patients and clinicians.

Developing a personalised approach to treatment-free remission

Dr Pagani has a vision – to develop a personalised approach to help indicate which patients can cease therapy with a high probability of maintaining remission, and which patients are likely to relapse and therefore need a new pathway to cure.

“This is the first attempt worldwide offering new personalised therapies to high-risk patients.”

“We hypothesise that there are two key barriers to treatment-free remission,” said Dr Pagani.

“One is residual CML stem cells in a sufficient number to overwhelm any immune mediated control, and the second is failure of the immune system.

“By determining the current barriers to treatment-free remission, we will develop new therapeutics targeting residual CML stem cells and modulating the immune system as a new pathway to cure.

“Expanding treatment-free remission to the majority of CML patients has the potential to improve quality of life, reduce drug-related complications, and reduce healthcare costs for many people living with long-term tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy,” said Dr Pagani.

“Our model of prediction has the potential to change clinical practice, guiding worldwide decisions about treatment-free remission, and improving the lives of many CML patients and their families.”

The challenge of eradicating residual disease in CML

Dr Pagani is studying how to eradicate residual CML stem cells, as a recipient of the Beat Cancer Project Mid-Career Research Fellowship, granted by Cancer Council SA.

TKIs are less effective in eliminating CML stem cells, which could persist despite therapy, become dormant, and be a source of relapse upon drug discontinuation.

“Eradicating the primitive CML stem cells which initiate and sustain the leukaemia is one of the toughest challenges faced by haematologists worldwide,” said Dr Pagani.

She has accepted this challenge and has started her battle against residual disease by studying the metabolism of the CML stem cells and how nutrients affect TKI resistance and cell proliferation.

By identifying the deregulated signals in a CML stem cell and their specific metabolic vulnerabilities, she aims to develop tailored therapies for CML patients which can target a fundamental process in CML stem cells and eradicate them.

Dr Pagani was recently awarded a grant* from the Leukaemia Foundation as part of its National Research Program.

“Receiving this funding is an honour and a privilege, and it will help me to offer a new pathway to cure for CML patients. I am very grateful to the Leukaemia Foundation and to patients and donors that are supporting my research.”

“My vision is not only to identify patients who can safely cease their TKI, but also to offer new therapies for patients with a predicted worst outcome. My vision is to reduce the number of patients suffering from this disease by finding a cure”.

Patient advocates contribute to research

Dr Pagani said consumers have an increasingly important role in research.

“They not only contribute to the planning stage of research, but also assist with lay summaries and the diffusion of the new knowledge, ensuring that the research findings are easily communicated to the other CML patients and to the community,” she said.

In 2019, in collaboration with her colleagues, Dr Yazad Irani and Jade Clarson, Dr Pagani created the first SAHMRI Myeloid Group which includes four CML patients and an AML patient.

“The contributions of consumers to my research is very important to me. My projects are shaped based on patients’ priorities. I have the unique opportunity to use my expertise and knowledge for addressing pivotal questions from CML patients, helping to improve their lives.”

Dr Pagani is President of the Association of Italian Researchers in Australasia and a passionate science communicator.

“I am concerned with giving back to the next generation of scientists and sharing the significance of my findings with the public.”

Saving lives in the lab and as a surf life saver

“No one deserves to be sick and suffer. I have devoted my life to helping people,” said Dr Pagani who works to save lives not just in the laboratory, but also at the beach, as a surf life saver.

At her local club at Brighton, she met Kevin Watkins, a SLS champion who was diagnosed with CML and myeloma in 2015. While he continues to take medication for myeloma, he is a CML patient who is now in treatment-free remission.

Kevin said, “I am happy that Ilaria is so investigative in her work”.

“As a CML patient, I am buoyed by the fact that she is widening the scope of traditional treatment and researching treatments that are specific to patients who respond, as well as don’t respond, to treatment,” Kevin said.

“We share a common passion for surf lifesaving and we are fighting together against cancer; Kevin as a consumer and me as a researcher, as well as saving lives at the beach,” said Dr Pagani.

She also is a competitive river rower, and since bringing her passions for science, sport, and photography to her new home in Australia, Dr Pagani has established a friendship group, has married, and she and her husband have two cats, Senna and Dovi.

* A six-month Strategic Ecosystem Research Partnership grant of $102,000.

Last updated on January 3rd, 2023

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.