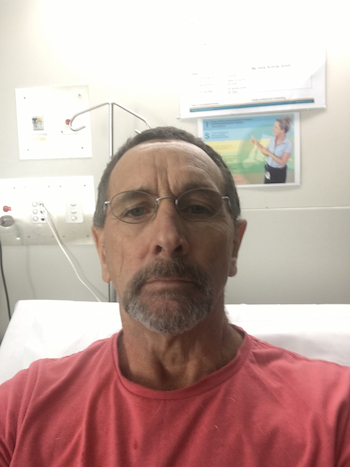

Diagnosed with MDS, AML, then MDS again

When Tony Wakely was diagnosed with MDS in 2017, he felt it was something he could live with. Then the MDS quickly transformed to leukaemia, which was “very scary”, but he accepted the diagnosis and he beat the AML. Being diagnosed with MDS again the following year, though,’ was “gut wrenching”.

This four-year journey began on Friday May 12, 2017 on the job as a machine operator at an aluminium extrusion company, where Tony’s wife, Karen, also works.

“I had a bit of a turn at work. I thought I had a TIA [a transient ischaemic attack, often called a mini stroke] so Karen took me home and I made a doctor’s appointment,” explained Tony, 61, of

Springfield, an outer western Brisbane suburb.

“The side of my face was a bit numb and I thought, ‘oh, that’s not right’.”

Tony’s GP arranged for him to have blood tests and he was told not to go back to work.

“I just thought we’d find out what was wrong and that it wouldn’t be much,” said Tony.

“You don’t think of things like MDS and AML, which I’d never heard of, but there you are.”

The following week, when Tony saw his doctor again, he was told he was ‘an anomaly’.

“I had high iron and was anaemic at the same time… something he’d never heard of before. He consulted me about sending my results to haematology at Princess Alexandra Hospital (PA).”

Tony’s diagnosis with MDS, then AML

“I got an appointment at the PA fairly quickly, so off I went. I’d never been to the PA before in my life,” said Tony.

While sitting in the oncology department, Tony’s thoughts were, “what the hell and I doing here? How am I in this situation?”.

“I got called in and a young registrar went through a whole pile of things and said, ‘we think it’s MDS’.

“Not wishing to appear ignorant, I said, ‘what the hell is MDS?’. She told me, and I sat there, saying, ‘you’re kidding me, aren’t you?’ [in rather more colourful language!].

“She said, ‘it’s the only explanation. It’s a form of leukaemia.’

“I said, okay, that’s fine, I can live with that. What do we do? And she said, ‘well, we’ll put you on a wait and see what happens’, on a 12-week cycle.”

Before heading home with Karen, Tony had another blood test, to keep an eye on his anaemia.

“Three days later they rang and said, ‘we’ve changed you from a wait and see, to we need to see you in six weeks’. I said ‘why?’ and she said, ‘things have changed’.”

When Tony went back in early-August “for a bit of a look-see” his blood results indicated things weren’t quite right and although his haemoglobin was “high enough” he had a bone marrow biopsy.

Later that day he got a phone call saying, “things are moving differently to what we thought”, and four days later Tony was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), with treatment to start in two days.

Tony has written extensively about his experiences with MDS and AML in a journal he calls Blood Wars, and which he shares with you here.

Dealing with his leukaemia diagnosis

“The MDS had mutated that quickly,” said Tony.” It was pretty scary, to be honest.”

“I could handle the MDS diagnosis because I was told ‘it’s still in the early stages’ and I guess they had a plan on what they were going to do with me.

“But when it was AML, it was… ‘just a sec’… and the only reason I didn’t go straight to hospital was because it was People’s Day at the Ekka [the annual Royal Queensland Show public holiday].”

So Tony had 24 hours to tell his boss he would be off work for longer than previously discussed, and to arrange his finances.

“It was very scary, but I accepted the diagnosis because you can’t change it. There’s no point curling up into a ball and going, ‘my life is crap’,” said Tony.

“You just go, ‘fine, what’s the treatment, what’s going to happen?’ and ask all those questions.”

Tony went to the PA the following day and began induction chemotherapy, followed by consolidation treatment, which he had as an outpatient except for the final two weeks when he kept spiking temperatures.

“They were treating me for the AML because it had morphed past MDS.”

He went into remission and was told he’d need to have a bone marrow transplant because he had the p53 deletion as well. Tony’s response to that finding was, “it doesn’t get much better than this does it?” [in slightly more descriptive language].

“So, I role with the punches and it turned out it wasn’t a deletion, it was a mutation of the p53 DNA strand.

“Luckily I was smart enough to ask all the questions you need to ask… what’s p53 doing? What’s this chemical that’s flowing through my veins? What are the next seven days going to do to me? and all the rest.

“I had a specialist tell me, ‘you’re not taking this disease very seriously Mr Wakely, because I just kept a happy face on all the time,” said Tony.

“And I said, ‘well there’s a whole lot of other people around here taking it seriously for me’.

“There’s no point in being depressed about it or dwelling on it and moping around.

“If you have a positive outlook on things, what can go wrong?

“I walked through the ward and thought how depressed the patients looked and decided, ‘no, that’s not going to be me’.

“So I got myself mobile, me and my pole, which I nicknamed Elvis – I hated that pole because I was attached to it – and we’d go walkabout.

“But you need to keep active. I was a fairly active person before this, then suddenly I was set up in a hospital bed, watching movies, reading books, and sleeping.

“The doctors came in one day and said, we came looking for you and you weren’t here’.

“I said, ‘no, I was out for a walk’, and they said, ‘no more walking past the end of the ward because you need your pain meds and your white cell counts are low again, and if you pick up a cold we’re back to square one. You’re in more danger now than you’ve ever been in your life’.

“The doctors put a travel ban on me because I was going all over the place.”

“So I thought, ‘can it get any worse than this’ [explicit language omitted].”

At the time, Tony didn’t understand what ‘neutropenia’ was.

“That was my problem. I didn’t understand it. My neutrophils had crashed down to .001 and I had nothing to fight anything with. At this point I agreed that I’d better listen to what the doctors say.”

Tony was transferred to the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital in October to start the lead-up for his transplant. Of his three siblings – two sisters who live in New Zealand and a brother in Sydney – only his older brother, Micheal, was a match for his allogeneic transplant.

He was admitted for the transplant, which was on 29 November 2017, and during the following three weeks, “nothing went wrong”.

“I considered myself extremely bloody lucky,” said Tony.

“One of the registrars there called me the most boring patient on ward because I didn’t have any mucositis, I didn’t have any fevers, no temperatures, no infections… I had nothing.”

And no graft versus host disease (GVHD), which Tony said, “led to the problem of where we are now”.

“The haematologist had said, ‘I’m happy to see GVHD because it fires up your immune system’.

“They don’t like to see a lot of it, but they like to see some reaction from the body,” said Tony.

Getting on with life after his stem cell transplant

During the 100 days post-transplant Tony had immunosuppressants and antifungals, “and you name it”. His blood results kept coming back saying everything’s fine, and bone marrow biopsies indicated the engraftment was successful. His blood type and rhesus had changed from A negative, to his brother’s, O positive.

“Everything seemed to be okay,” said Tony.

He was given the okay to go back to work in mid-2018 but as he was still immunocompromised and hadn’t yet had any vaccinations, and it was the middle of flu season, Tony waited until August before returning to work.

“I was suffering a bit of fatigue from the transplant and it took a while to adjust, but it was great to be back amongst people and doing things,” said Tony.

However, the months from August to Christmas were “testing times”.

“One of the nurses at the Royal said, ‘having a transplant is like being in a car crash and having every bone in your body broken and staying six months in ICU… that’s the amount of trauma and stress that’s placed upon your body’.”

Tony’s fatigue issues continued, and in April 2019 he got shingles, in his mouth and down the side of his face, which affected his ability to eat, and he had nine days off work.

All his life Tony had been a hepatitis B carrier and prior to his transplant he had been put on medication to suppress the hepatitis. In June, Tony asked his haematologist, ‘what’s my hepatitis status, is it still inactive?’

He had a serology test, and three days later, Tony was told the hepatitis B had become active due to the changing of his blood type, and his response was, “what else can go wrong?”.

“And it did go wrong. In December, I found out I’d relapsed back to MDS, which was unusual because all the blood tests and everything were saying that everything was fine”.

“My haemoglobin got up to a 120, my platelets were at about 300 and everything was where it was should be.

“But a bone marrow biopsy at the end of November picked up the dysplasia. It appears that 5% of my DNA managed to survive the transplant and that 5% had MDS in it,” Tony explained.

“My haematologist was as aghast.

“I had the MDS coming back.”

“It was gut-wrenching, to be honest, to be told that after all the hard work.”

For a whole year, there had been no indication there was any dysplasia until that bone marrow biopsy.

Initially, Tony had been rung at work and told there was ‘an anomaly’, but they weren’t too concerned at that stage, and were waiting on the DNA results.

“But he rang a few days later and said, ‘it’s not good, you need to come in and we’ll discuss what’s going to happen next’. That was December 11, 2019 and that was the last day I worked.

“It turns out that the p53 deletion that everybody thought I had, was actually a mutation, and that mutation didn’t go away with the bone marrow transplant. It had been hiding in the background.”

MDS treatment begins

Tony began treatment for MDS. He was put on azacitidine (Vidaza®) but had to stop this treatment as it was doing “too good a job” and was driving his blood counts down. So, in April 2020, he went on interferon (Pegasys®) for 12 weeks.

“When my blood showed signs of recovery, we managed to get my brother up here during COVID so we could do donor lymphocyte infusions*.

“This was done over the next four months, trying to fire up my T-cells to see if it would help fight the MDS, in conjunction with a single dose of azacitidine,” said Tony, who had four DLIs, one per month until November 2020.

“I don’t think it worked at all. I think it was more of a trial, but I don’t think they got the response they wanted,” said Tony, so he went back to having monthly injections of azacitidine until February 2021.

“Then they declared the azacitidine wasn’t working anymore. They’d lost control of the MDS. My MDS cells had gone from 6% to 22%.”

In March, Tony started venetoclax (Venclexta®) – four pills a day – which he accessed on compassionate grounds, as this drug was only listed in Australia for CLL, at that stage.

When he spoke to MDS News, in late-April, his dose of venetoclax had been reduced as he was fighting a fungal infection that had developed in his lungs. He had been in and out of hospital a couple of times.

“The venetoclax is the last option,” Tony said stoically.

When he asked his haematologist how long he’d take venetoclax for, Tony was told, “for as long as it works”.

“I don’t know what the plan is to be honest moving forward. I’ve got, at best, 12 months,” said Tony. He had received that news three weeks earlier.

“That’s my prognosis at the moment. I’m living with it. That’s what I’ve accepted. I think it’s naïve to hide from the truth of what could happen. And that’s what it is.”

Telling his three siblings “the bad news” was met with “sheer disbelief” and “utter shock”.

“I said, well, this was always going to be the inevitable outcome. I thought I had a little longer – 12 to 18 months longer than what I’ve got – but I haven’t,” said Tony.

“At the moment everybody seems to be happy with the blood counts that I’ve got, which are poor at best. But they all seem to think that that’s okay.”

The one thing that’s truly depressing Tony is his weight loss; a side effect of the venetoclax which speeds up his metabolism.

“I’ve seen a dietitian and I eat like there’s no tomorrow,” he said.

“I’ve gone from 90kg to 78kg. I haven’t been this thin since I was 24. So, that’s the scary part. It scares me more than the diagnosis and what I face ahead of me.”

Living life with MDS

During February and March, Tony had become “quite sedentary”.

“I’d just get up, sit down and do nothing all day and I was having blood transfusions as my Hb was getting low and I was using that as an excuse to do nothing as well.”

But at the end of April, when Tony was sitting in hospital, he made a decision, “enough is enough”.

“Enough of sitting around, starting to feel a little bit sorry for myself. It’s time to get off my …. and do something, so I’ve gone back to attacking life as I should have been which is to grab it by the horns and just go for it.”

This means a little exercise and “doing the things I’ve been making excuses not to do, like mowing the lawns”.

“I’m actually leading a normal life, sort of. I know this is about as normal as this is going to get for me. So just leading a normal life has been making me really happy at the moment.

“I feel brilliant at the moment, to be honest. This is the best I’ve felt in weeks,” said Tony, which he put down to a combination of the venetoclax, the antifungal infection (voriconazole) and having had a blood transfusion a few days earlier.

“The antifungal enhances the venetoclax, so I said, ‘why don’t we just do a combination of the venetoclax and voriconazole forever, and I’ll be fine!” said Tony jokingly.

“If I can stay away from hospital, I’d like to go and see my brother, and take my wife away and revisit things we haven’t done for a while around south-east Queensland.

“Karen turns 60 this year and I was going to take her up to Hervey Bay for the weekend but it all fell apart because the venetoclax had just started.

“I know I can’t cross the Tasman to catch up with family and friends like I wanted to,” said Tony who is a New Zealander.

“I’m on weekly transfusions for my Hb, so I’ve said to everybody, ‘you know where we live, come and see me’.

“Karen is still working, and my old boss is her boss and he’s quite understanding of the situation,” said Tony about her taking time off work.

“The whole company has been supportive. When I originally got AML, they held my job for me.

“I wanted to go back to work, I really did, but as this thing has progressed, the reality kicked in about August last year that I would probably never return to work, so I’m on income protection.”

Tony is proactive in self-advocating

Tony ensures his tests and treatment arrangements and decisions enhance his quality of life and are convenient.

One day when he had a CT scan and was due to come back the next day for a bronchoscopy, Tony spoke up, saying he wanted to be admitted to hospital so Karen didn’t have to take more time of work to ferry him back and forth to the hospital.

Another time, when he was discharged on a Monday and asked to come back the next day for another procedure, his response was, “no, I’ve had enough of hospital, we’ll do it Friday”.

He also suggested a change to his blood transfusion protocol, from two bags a fortnight – when he’d end up spending the weekend before his transfusion feeling tired and falling asleep on the couch – to one bag a week.

“If I’m going to add some quality of life, I don’t mind giving up a day a week, so I can be reasonably healthy and we can do things together on the weekend,” said Tony.

“Otherwise, it’s not living, it’s just passing time.

“I’ve become more proactive since I’ve been on venetoclax because I want to make sure this works for as long as it possibly can.”

Support from the Leukaemia Foundation and others

“I’m one of those fiercely independent sort of people and have never needed anything from the Leukaemia Foundation,” said Tony, who had contact with a couple of Leukaemia Foundation blood cancer support coordinators early on.

“Nicole Douglas came to see me at the PA when I did my induction chemo, just to have a chat, to see where I was at and what I was up to. She was great, better than the social workers.

“I go on the website, and at one stage I was on both the MDS and AML Facebook groups, where you’ve got other people with the same disease which helped a lot and have been rather good.

“I’ve donated to support you because I do have leukaemia.”

“The person who has inspired me the most is my cousin in New Zealand and at one stage he was over here, and we caught up. He was diagnosed with a stage 4 brain tumour. He used to text me, to see how I was going and to perk me up a bit every now and again.

“He had the same positive outlook on everything that I’ve got, and he didn’t let his disease rule his life. He knew the inevitability of his outcome as well. He only had 18 months tops, and he died on New Year’s Eve, 2019. He was 58.”

“Look, it’s what it is. I remember, as a young man, reading in a Reader’s Digest that when you accept the inevitability of your own mortality, the rest of your life becomes very easy. That’s a philosophy I’ve had all my life,” said Tony.

“It’s not being naïve or stupid, it’s being practical. You can’t give in to this, you’ve just got to keep going for as long as you can.”

“I think you just pack yourself in for the ride and see where it takes you. If you start to worry too much, you’re starting to lose the battle.

“It’s been an interesting journey because I’ve learnt so much. It’s given me a greater knowledge than if I hadn’t had the experiences I’ve had over the last four years.”

Tony has written about those experiences in a journal on his computer, cataloguing what he’s been through. “It was a way of stress relief,” said Tony, and he has chosen to share this with you. It’s called Blood Wars: My Body’s Rebellion.

*A donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) is a procedure in which lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) from a donor are given to the patient with blood cancer. DLI is a potential treatment option in people who have had a previous treatment with an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Last updated on February 22nd, 2022

Developed by the Leukaemia Foundation in consultation with people living with a blood cancer, Leukaemia Foundation support staff, haematology nursing staff and/or Australian clinical haematologists. This content is provided for information purposes only and we urge you to always seek advice from a registered health care professional for diagnosis, treatment and answers to your medical questions, including the suitability of a particular therapy, service, product or treatment in your circumstances. The Leukaemia Foundation shall not bear any liability for any person relying on the materials contained on this website.