Tony’s in remission after CAR T-cell therapy – his last option

The day Tony Gillen was told he had ALL, “it didn’t really sink in”. So, he called his wife, Leanne, on his walk back to work, attended meetings, and didn’t head home until 6pm.

That was 11 December 2018, and until then, his only symptoms had been problems with his legs and feet.

“I just thought, being an old footballer, I was starting to get some arthritis, so I ended up going to the doctor,” said Tony.

After a “precautionary blood test” his GP called later that day saying, “come back in tomorrow”.

“That’s how it all started,” he said.

Tony’s diagnosis with B-cell Philadelphia positive (Ph+) ALL stopped him in his tracks.

He was 52, had a “lovely wife” and two children, Alex and Elisabeth, then aged 19 and 11. For 26 years, he’d worked in the hospitality industry, the last 14 of them at The Builders Club, at Wollongong, where he’d worked his way up to the role of operations manager.

Then, a week after telling his employer about his change in health, Tony spiked a high temperature and was told by his haematologist, “you can’t go to work anymore”. It’s now 28 months since he finished work.

Initial treatment and a bone marrow transplant

The timing of his diagnosis–just before Christmas–wasn’t conducive to starting treatment and, as Tony’s platelet count was critically low, he spent the next three weeks stuck at home, watching Netflix, with the air con on.

Finally, on January 10, he was admitted to hospital and started an aggressive form of chemotherapy, which he completed in May 2019. Then he had a six-week break before having a bone marrow transplant in Sydney on June 26. Tony’s younger brother, Stephen, was his donor, and his only match among his four brothers.

The weeks after his transplant wasn’t an easy time for Tony.

“I didn’t enjoy it at all. I got sick, I got infections.

“Every time I’ve been in hospital I’ve ended up with high temperatures, mucositis, various infections or this, that, and the other. I’m not one of those people that just skip through things… I tend to cop it.

“I spent like 122 days in hospital from January until I got out [after the transplant] in mid-July.

“By October, I had 100% donor cells. There was no trace of leukaemia which was great, fantastic, but from November to December, slight traces appeared again.

“They weren’t too worried because they initially thought it could just be residue,” said Tony.

But the presence of leukaemia gradually increased, and on 20 June 2020 “things had gone pear-shaped”.

“I’d actually gone to hospital because I thought I was having graft versus host disease. I had show-stopping cramps, diarrhoea, and belly problems.

“They did some more tests and told me I had relapsed,” explained Tony.

“It sat me on my tail, there’s no two ways about that, because I was almost ready to return to work and to try and get my life back on track, to being the father of the family. And that didn’t happen.”

What happened after Tony relapsed

Tony’s initial treatment had included imatinib (Glivec®).

“They decided to go to the next level,” said Tony about his next line of treatment, dasatinib (Sprycel®).

But after a month, when that wasn’t working, he was admitted to hospital in Wollongong for a combination of targeted therapies; blinatumomab (Blincyto®) and ponatinib (Iclusig®) during July and August.

“It seemed to be working initially, but the side-effects were a bit much for me and I accidently tore out the picc line in the shower. But it wasn’t really working, so they decided I wouldn’t go back on that.”

Tony was referred to Sydney again in September, and by October his leukaemia had started to jump up again. Another bone marrow transplant was being teed up but there were doubts about its success because of how the leukaemia was progressing.

“I was running out of options,” said Tony.

Getting on a CAR T-cell therapy clinical trial

Then his haematologist, Dr Barbara Withers, in Sydney, found a clinical trial for CAR T-cell therapy in Melbourne.

“I was fortunate enough to get on that trial,” said Tony.

“I was the first person in Australia with relapsed ALL to do this trial.”

He was referred to Melbourne during the lockdown and due to the paperwork involved, his arrival was delayed by a week. He began having tests and screens and had a bone marrow biopsy in early November.

“I was only down there about three days when they told me my leukaemia had reached a point where they didn’t think it was safe for me to go back to Sydney,” said Tony.

He was admitted to the Royal Melbourne for more intensive chemo in an attempt to control his leukaemia so he could be accepted on to the trial.

“Unfortunately, it didn’t really work. All I did was got sick. It didn’t have a major impact on the leukaemia like it had in the past,” said Tony.

By this stage, it was early December.

“My wife and family moved down to Melbourne to be with me over the Christmas period. They were down for about 12 weeks,” said Tony.

During this time, the Gillen family stayed across the road from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre where Tony was treated, just a 200m walk, but sometimes he had to stop several times just to get there.

“Initially, we had some help from the Leukaemia Foundation,” said Tony. This was prior to his accommodation and travel costs being met by the clinical trial sponsor.

While Tony waited to hear about his eligibility for the trial, his medical team put him on another immunotherapy drug, inotuzumab.

“Now, to their credit, the company conducting the trial and the doctors in the medical team could’ve just knocked me back, because there was no way my [leukaemia] levels were within the range they were looking for.

“No one wants to spend that money on an unsuccessful trial, but they persevered with it and, God love them, the trial went ahead.

“I can’t remember the exact date they took my T-cells,” said Tony, “things got a bit fuzzy down in Melbourne. I wasn’t handling things at all well.”

The return of Tony’s T-cells, side effects, and response

His harvested T-cells went off the U.S. to be re-engineered and the wait for their return was nerve-raking, with Christmas, COVID, and international travel all involved.

The initial infusion date for Tony to be given his genetically modified T-cells was December 28, but this became January 5.

“There was a bit of apprehension about whether they could get the cells out of the U.S., but they were able to,” said Tony.

“I was grateful beyond measure to have my family there, just to have the people around you who you love makes a big difference,” said Tony, who had spent the previous three weeks in Melbourne by himself.

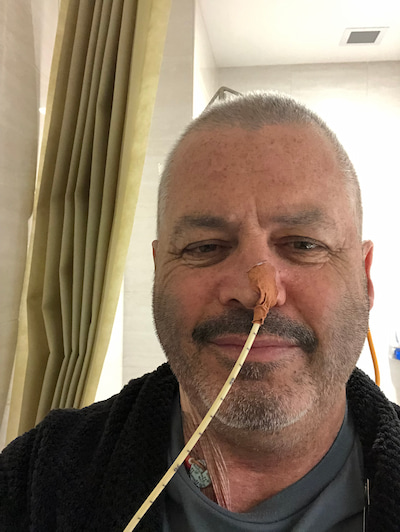

Having the T-cells put back in “was a bit anticlimactic”, he said.

“Whereas it took four hours [of apheresis] to take the T-cells out, it took like 10 minutes–pushing the syringe every two minutes–to get them in.

“And it wasn’t even a big syringe. I was expecting a horse needle, but it was only a little needle!”

Tony was then monitored for side effects and treatment response.

“Initially, they keep people in hospital for three days for observation, because of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) which is one of the biggest and potentially fatal side effects.

“I was in there for a whisker under three weeks,” he said.

“The doctors did warn me, because the leukaemia in my system was so prevalent, that I’d get a decent hit [of CRS] and they weren’t wrong.

“By the third day I was regularly throwing out [temperatures of] 39.5°, 39.6°,” said Tony.

“I had temperatures, but l felt good and wanted to do things, which was sort of weird. I wanted to get out, but I wasn’t allowed to.”

Tony was also checked for neurotoxicity effects. He had neurologic tests (ICANS*) every four hours, including at midnight, where he was asked questions, had to write things down, and point to parts of his body or objects in his hospital room.

“And a neurologist came and saw me once a day,” said Tony who was discharged and went home to Wollongong on February 15 this year.

He flew back to Melbourne twice, for weekly visits to have blood tests and a consultation, and now flies down for monthly consultations.

“This is the new normal and I am just happy to be alive and happy to spend time with my family,” said Tony.

In early February, when Tony asked his medical team, “how is this going”, they said they had to wait until he’d had a bone marrow biopsy to get that information.

“Then they said, ‘there’s nothing, we can’t find any leukaemia, you’re in remission’.”

“No minimal residual disease. So yeah, it’s all good,” said Tony.

“Now, the first question I ask after all my blood tests is, ‘am I still in the clear?’

“It’s still very, very early days.”

Tony’s been working on getting his body back with mild exercise, a pre-dawn morning walk, and a bit of housework.

And, after not being behind the wheel of a car for more than six months, he was cleared to drive in early-March.

Support from the Leukaemia Foundation

Since his initial diagnosis, Tony and Leanne have been supported by a range of Leukaemia Foundation’s services–transport, accommodation, and practical support–facilitated by the Blood Cancer Support Coordinator in their area, Snezana Djordjevic.

He’s also joined three online support groups on different subjects that he said, “were most helpful”.

“At the first support session, everyone was talking and sharing their story and I just cracked. I bawled like a baby and didn’t even know why. So obviously, I still had things to address myself about my relapse.

“After I relapsed, I didn’t take it at all well. I was pretty shattered with the realisation that I had to put my family through it all again. My head wasn’t in a good space.”

This was when Snezana connected Tony with a Leukaemia Foundation grief counsellor, Donita Menon.

“She helped me refocus and concentrate on what’s important,” said Tony.

And now that Tony’s income protection insurance is finished, Snezana is helping the Gillen’s access financial advice on matters such as superannuation.

While Tony wants to get back to work, his doctors have cautioned against returning to an industry where he deals with lots of people, due to potential issues with this immune system.

“Working with hundreds of patrons on a Saturday night, or something like that, wouldn’t be good!” he said.

“But hospitality is the only thing I’m qualified to do, so I’ve got to look at other avenues.

“We’ve still got a bit of a mortgage. That was one of the things that plagued me last year, after I relapsed and even before I started treatment.

“If I passed away my family would be financially secure, no problems. But if I survived and didn’t have a job, I’d be a financial burden to my family. Getting early access to my super to pay the mortgage off would be one less thing to worry about,” he explained.

“I’m feeling great, and grateful beyond measure,” said Tony about the “amazing people” on the medical teams at Wollongong, Sydney and Melbourne, and his family, who “put their lives on hold just to make sure I was okay”.

* Immune Effector Cell-Associated Neurotoxicity Syndrome (ICANS) assessment